I have this particular process that I do for writing a talk like this. I try to start it a month out, but usually I start it two weeks out. I sit down and try to write the entire thing as a long essay. Then I adapt it and evolve it. The really nice thing about doing that is that I have this history of my thoughts around marketing and AI over the last three years.

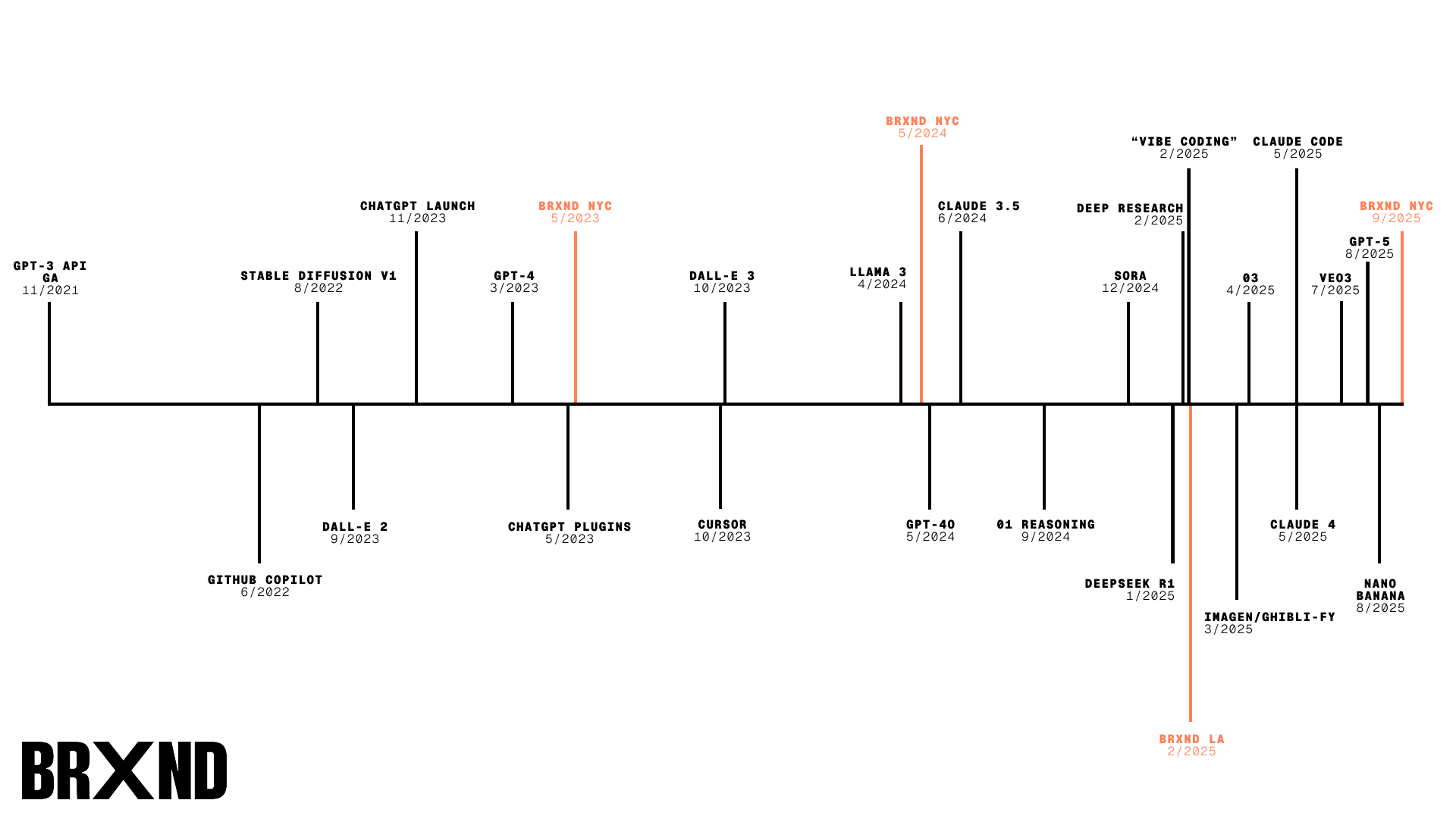

As part of putting this together, it was fun to look back at this journey. It’s kind of amazing how early it is in this adoption of AI. We started the conference three years ago. Whether you put the beginning at when ChatGPT came out, which was basically right after we started the conference, or when the API for GPT-3 went GA—it’s kind of amazing to look at. As much as has changed, I actually think a lot has stayed fairly constant.

Alephic Newsletter

Our company-wide newsletter on AI, marketing, and building software.

Subscribe to receive all of our updates directly in your inbox.

Just to put it in perspective where year three looks like: this is what year three looked like for mobile. Year three in mobile was the first 4G iPhone. It was 10 billion downloads in the app store. A billion dollars went out to developers. It was the year that Instagram, Netflix, and Find My iPhone made it on. I think it’s good to keep these things in perspective as we think about where we’re at.

The Four Truths

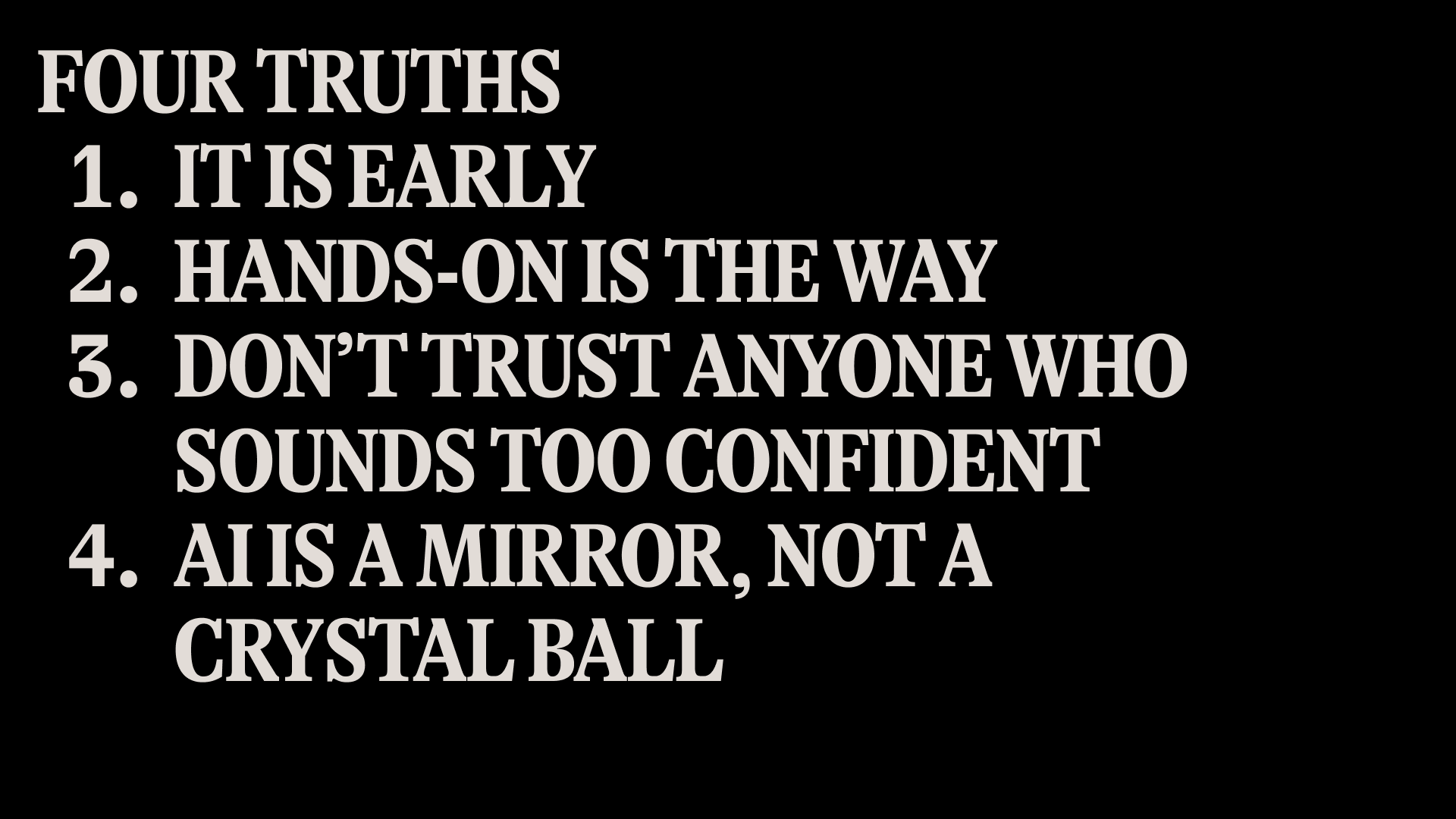

Going back and looking over those talks, I really had these four strings that I feel really good I’ve been saying for the last three years.

The first one is that it’s early.

The second one is that hands-on is really the only way to get a feel for this stuff. This is a fundamentally counterintuitive technology. It’s new, it’s different. The only way you can really get to understand it is to get your hands on a keyboard and actually play with it.

You can’t trust anybody who sounds too confident. There’s a tweet from a couple years ago that I constantly reference: the thing about playing with AI and keeping up with this world is not so much that you gain this magical foresight for the future. It’s that you get really good at detecting everybody else’s bullshit. I continue to believe that. Anybody who confidently asserts where we’re going to be in six months or 12 months or two years or five years is absolutely lying to you. You should approach any of that with deep skepticism, including from me.

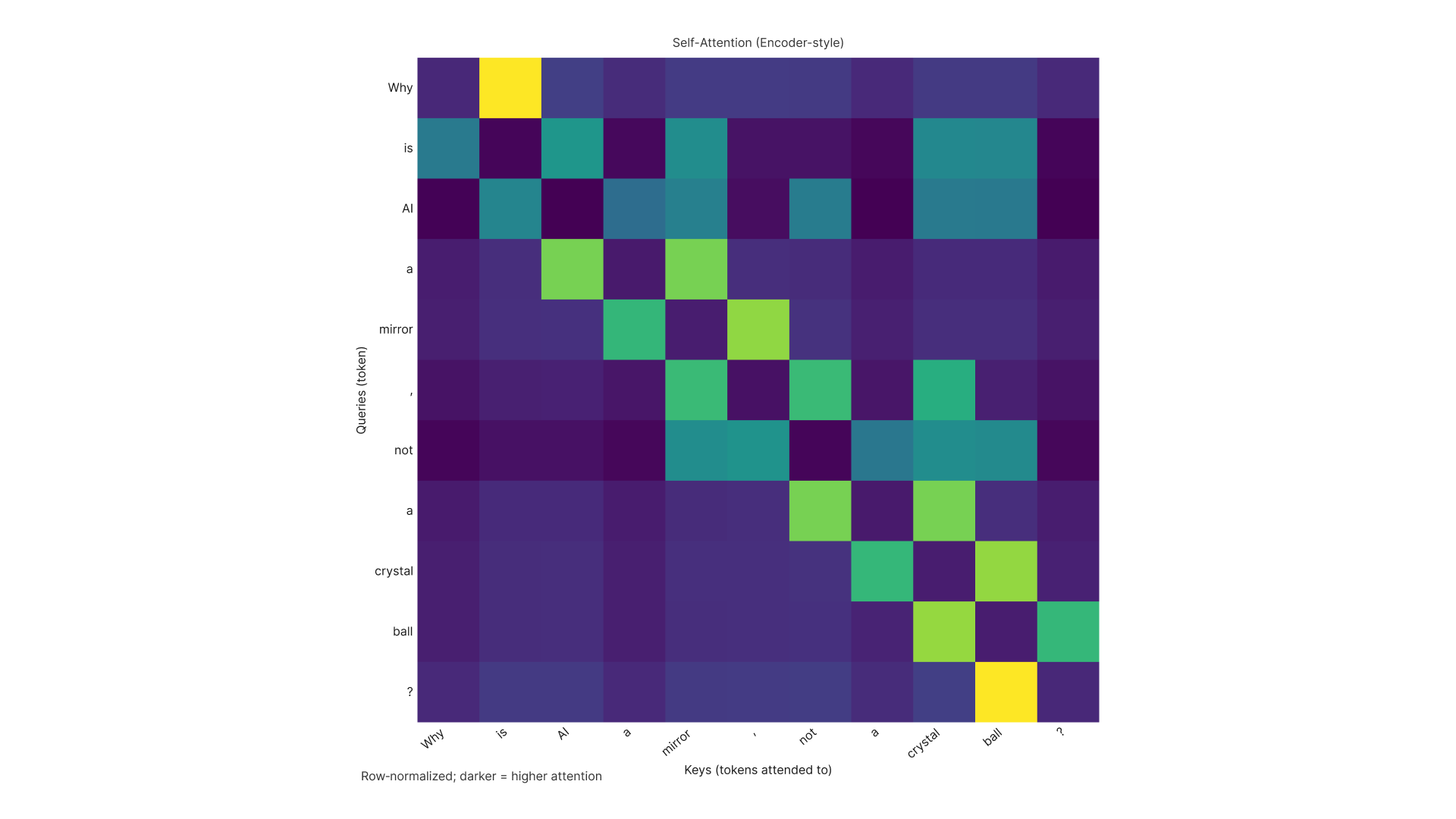

And then finally, AI is much more of a mirror than it is a crystal ball. This one is one that I’ve been thinking about for a while.

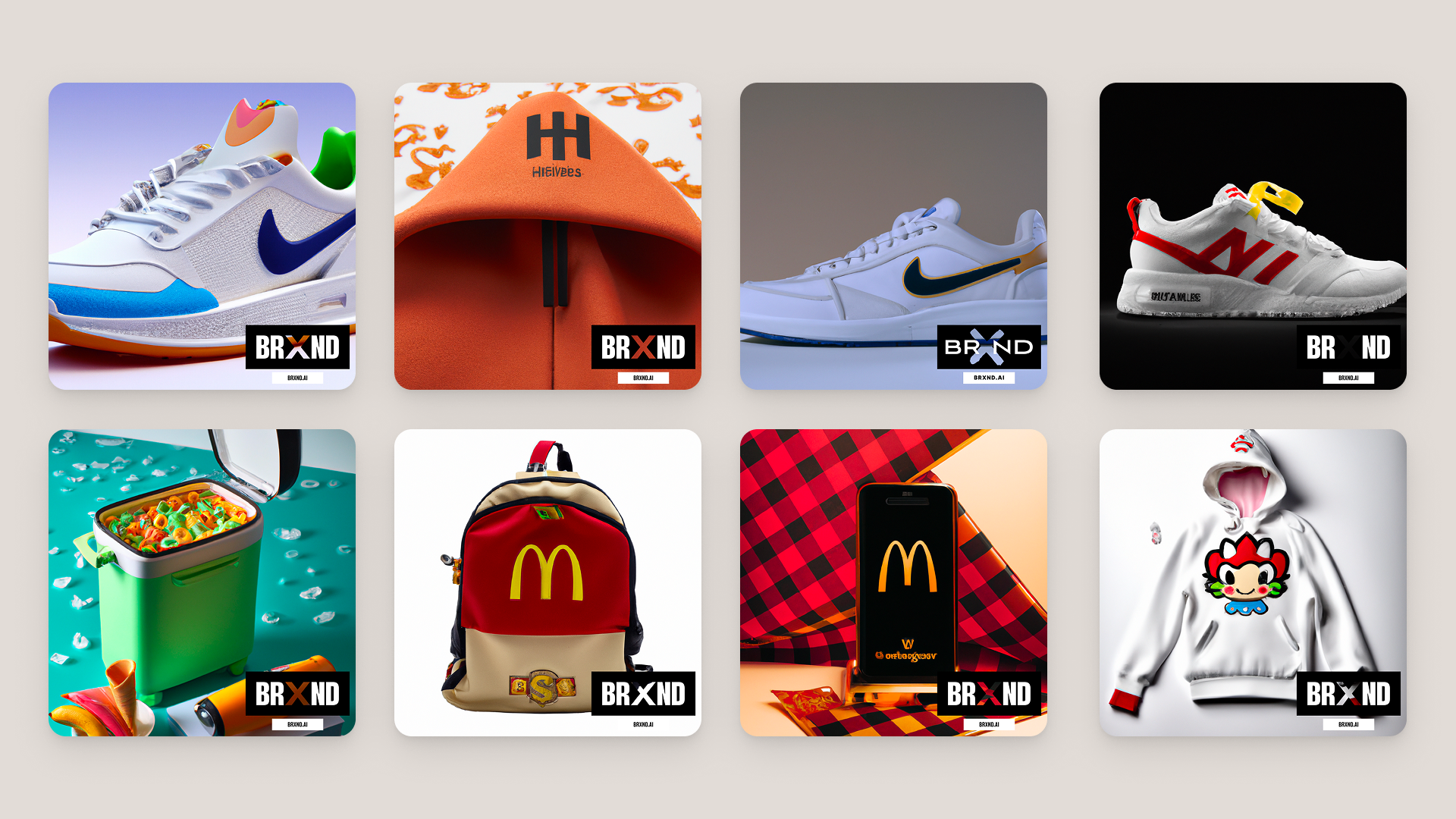

Slide 16: AI-generated brand collabs grid - Nike x Balenciaga, Supreme x Hermès

One of the very first things I did when I got my hands on the DALL-E 2 API and GPT-3 was build this collabs experiment. You could take two brands and smash them together and it would build these cute little brand collabs. It was of a moment, 2022.

What really struck me—and it’s actually what made me do all of this—was that good brands made better images. That sounds kind of trite at first. Of course good brands made better images. But when you think that these models start from nothing, they have no understanding of the world, that they still came to the same conclusions about what good brands are that I had.

Ultimately, good brands are built on consistency and distinctiveness. That’s kind of how these models get trained. They find those patterns. The stronger those patterns are, the better they’re reflected back in the models.

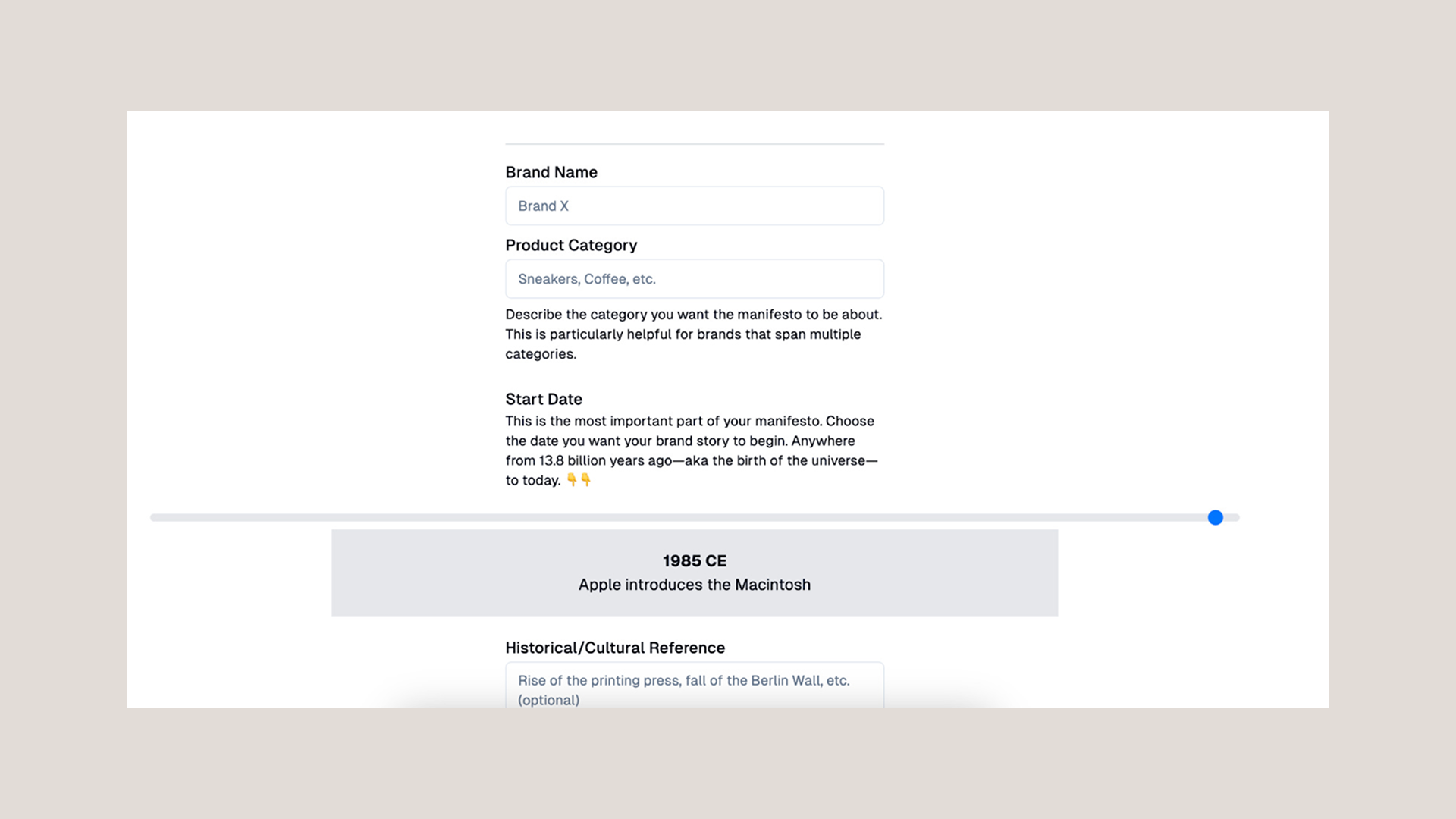

The flip side of that was I built a manifesto generator just as a fun game with a creative director friend of mine a couple years ago. One of the bits of negative feedback I got was: isn’t it kind of sad that we’re going to let AI write these manifestos? That these important brand documents should be given up to the AI?

My feedback to that point was: this only works because everybody writes the same manifesto. If every manifesto didn’t sound exactly the same to begin with, if you weren’t already the AI, then it never would have worked to begin with. I think we have to turn it back on ourselves.

The Narcissus Myth

Marshall McLuhan—he’s a favorite thinker of mine—in Understanding Media talks about the narcissist myth. He talks about how it’s frequently misinterpreted. We all think of Narcissus as this person who fell in love with himself, but actually Narcissus looks in the water and doesn’t recognize himself.

The root of the word narcissist is the same as the root of the word narcotic. It’s numb. He was numb to his own reflection. I think that’s kind of us. We don’t see ourselves in this thing immediately. We complain that it’s too bureaucratic, or it sounds too corporate, and we don’t realize that’s what we sound like.

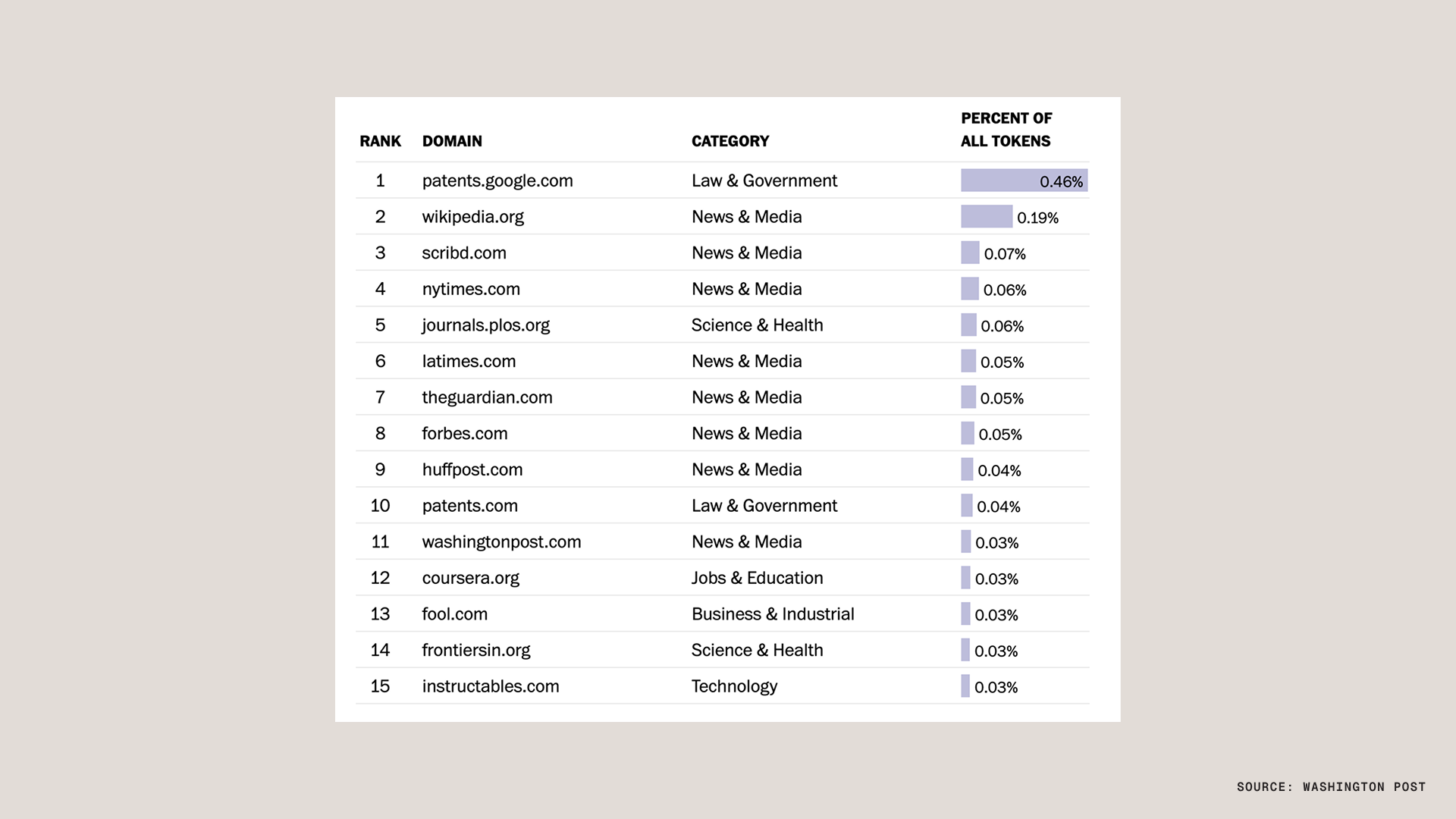

Obviously, this is not our whole selves. This is a representation of us as we exist on the internet, mostly. These models are trained on a corpus largely based on a thing called the Common Crawl. When the Washington Post went and looked at C4—a clean subset of the Common Crawl—what they found was that the number one source of tokens in C4 was patents.google.com.

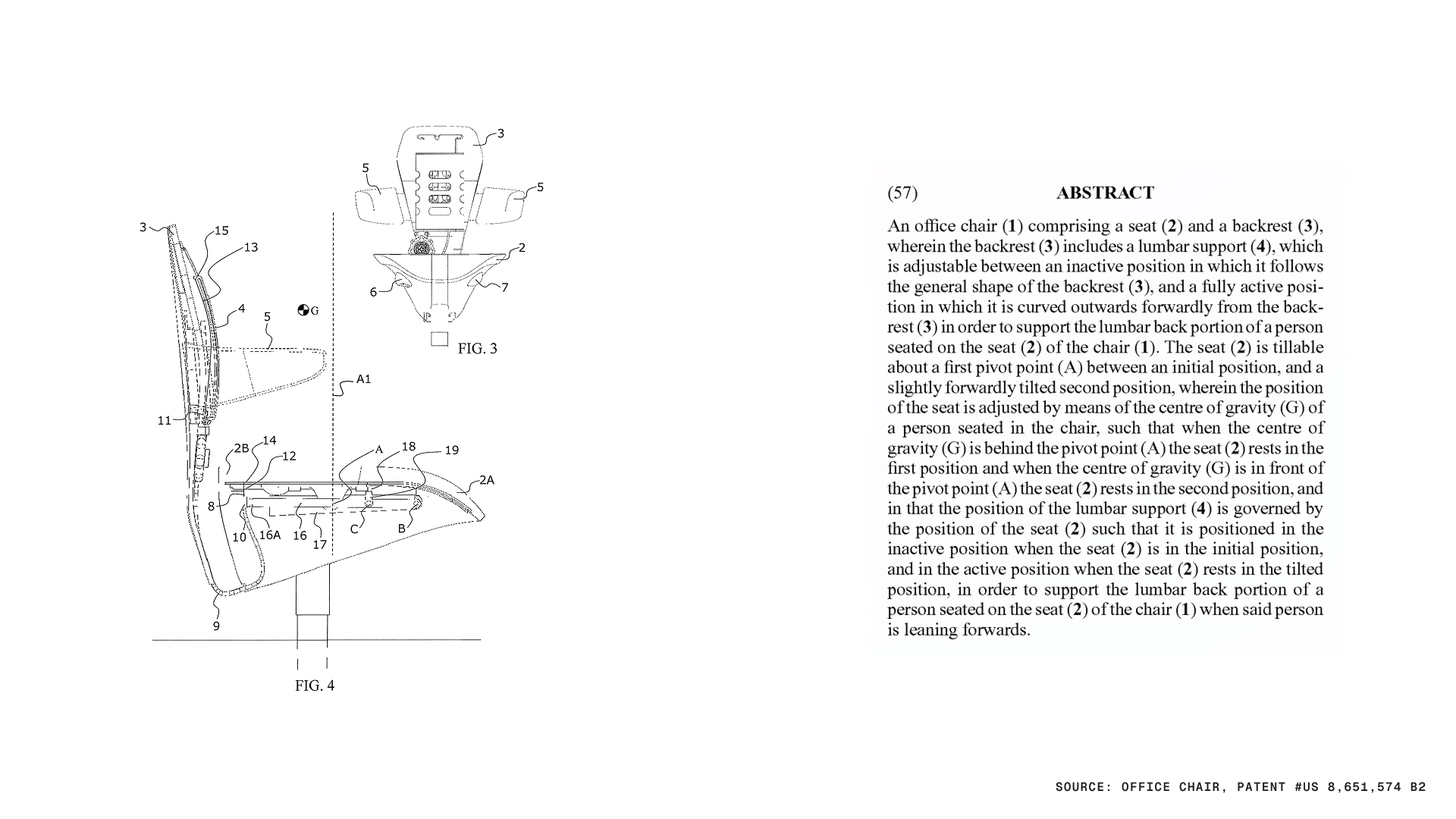

If any of you have ever read a patent application, you will know that they are the most excruciating way to describe anything that exists on the planet. This is an office chair comprising “a seat and a backrest, wherein the backrest includes a lumbar support, which is adjustable between an inactive position in which it follows the general shape of the backrest, and a fully active position in which is curved outwards forwardly from the backrest in order to support the lumbar back portion of a person seated on the seat of the chair.”

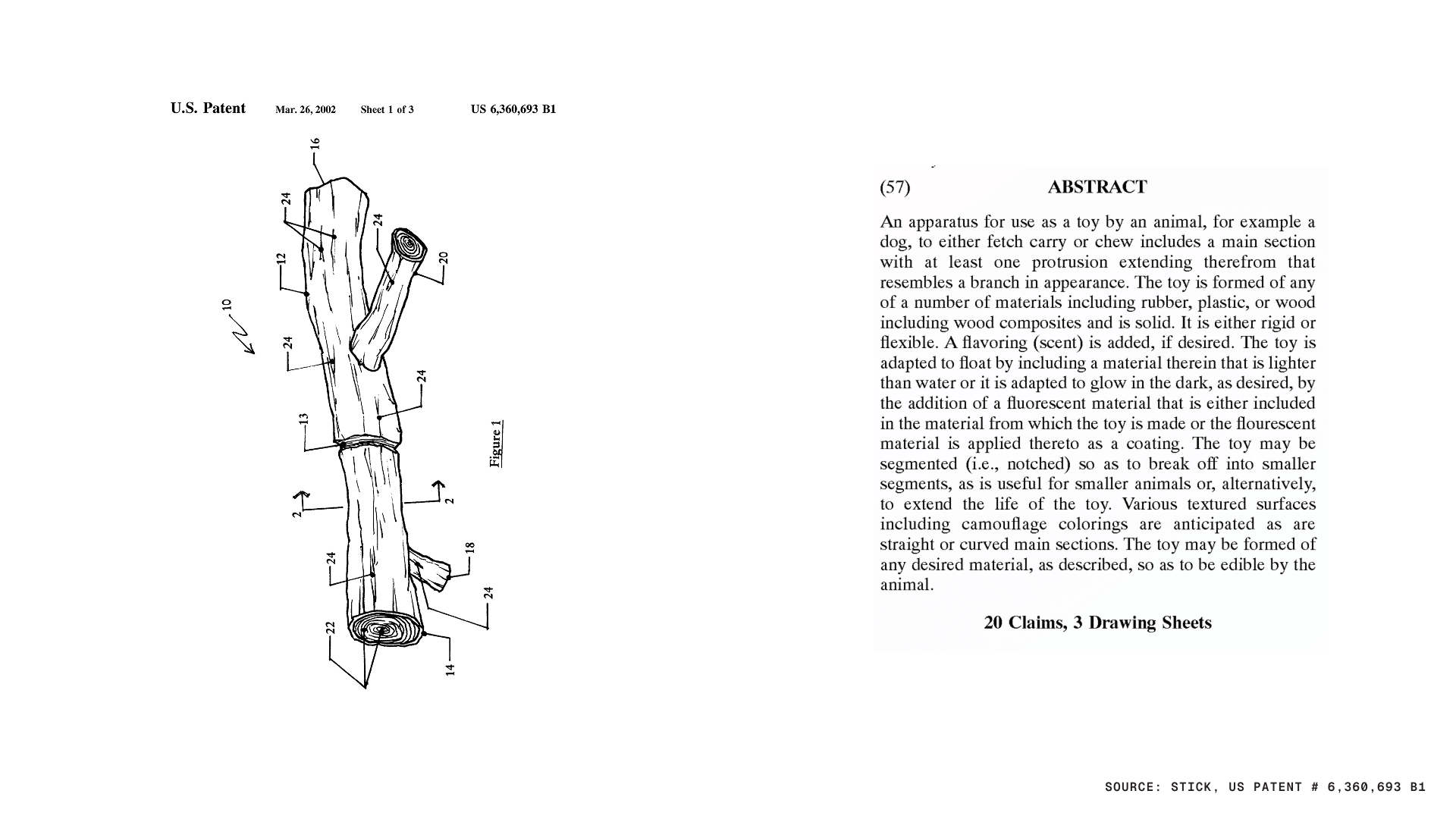

Or when I asked AI to find me an even more ridiculous one, it found me a stick. This is a more recent patent application for a stick: “an apparatus for use as a toy by an animal, for example, a dog, to either fetch or carry, chew or chew, includes a main section with at least one protrusion extending therefrom that resembles a branch in appearance.”

This is what we train these models on. We train them on text like that. That’s the single biggest set of tokens that exists in C4. We are narcissists and we’re staring into the water and we’re seeing reflected back to us an office chair.

Simple Sabotage

But where did we learn this? How did we come to be so bureaucratic?

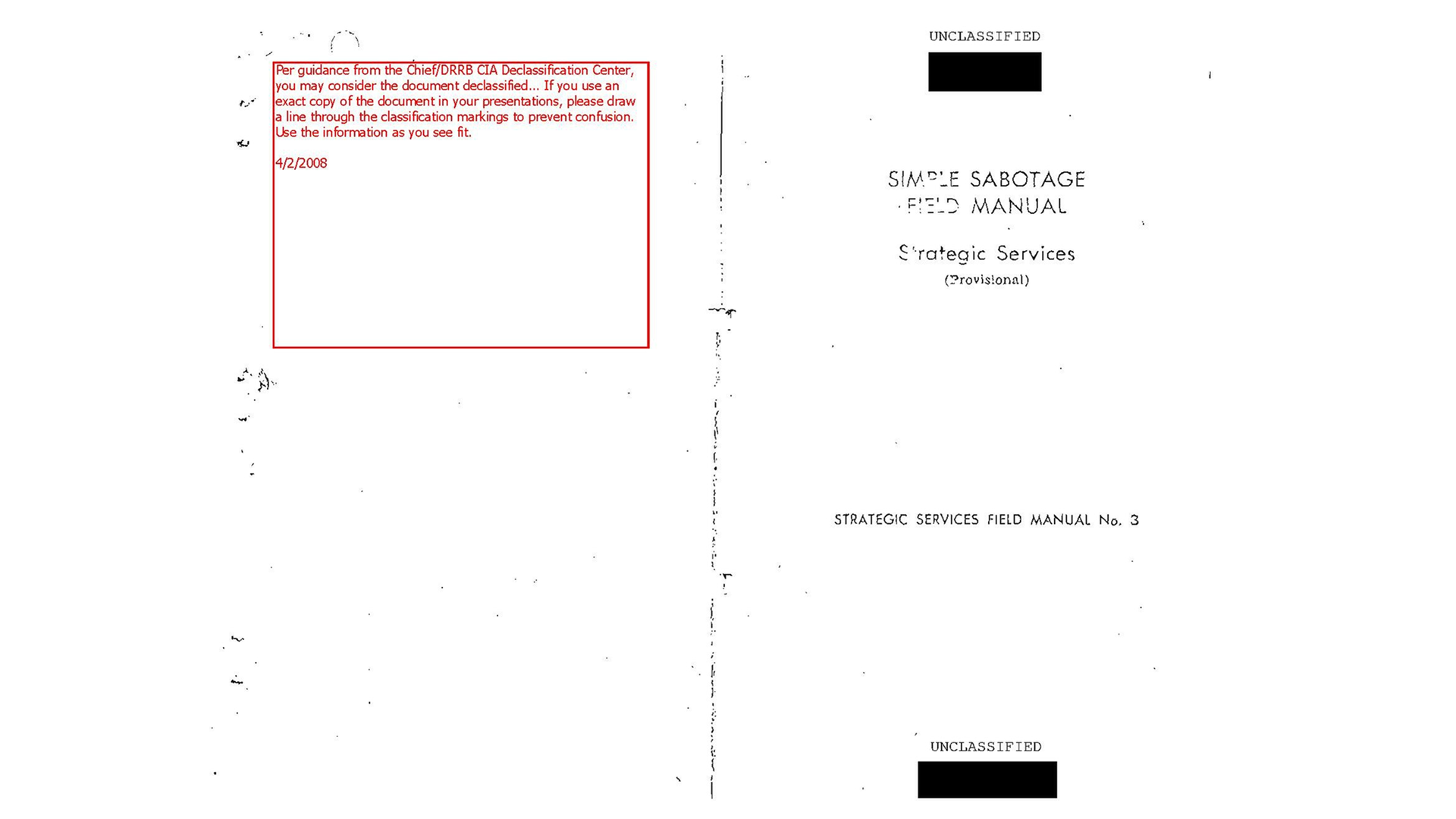

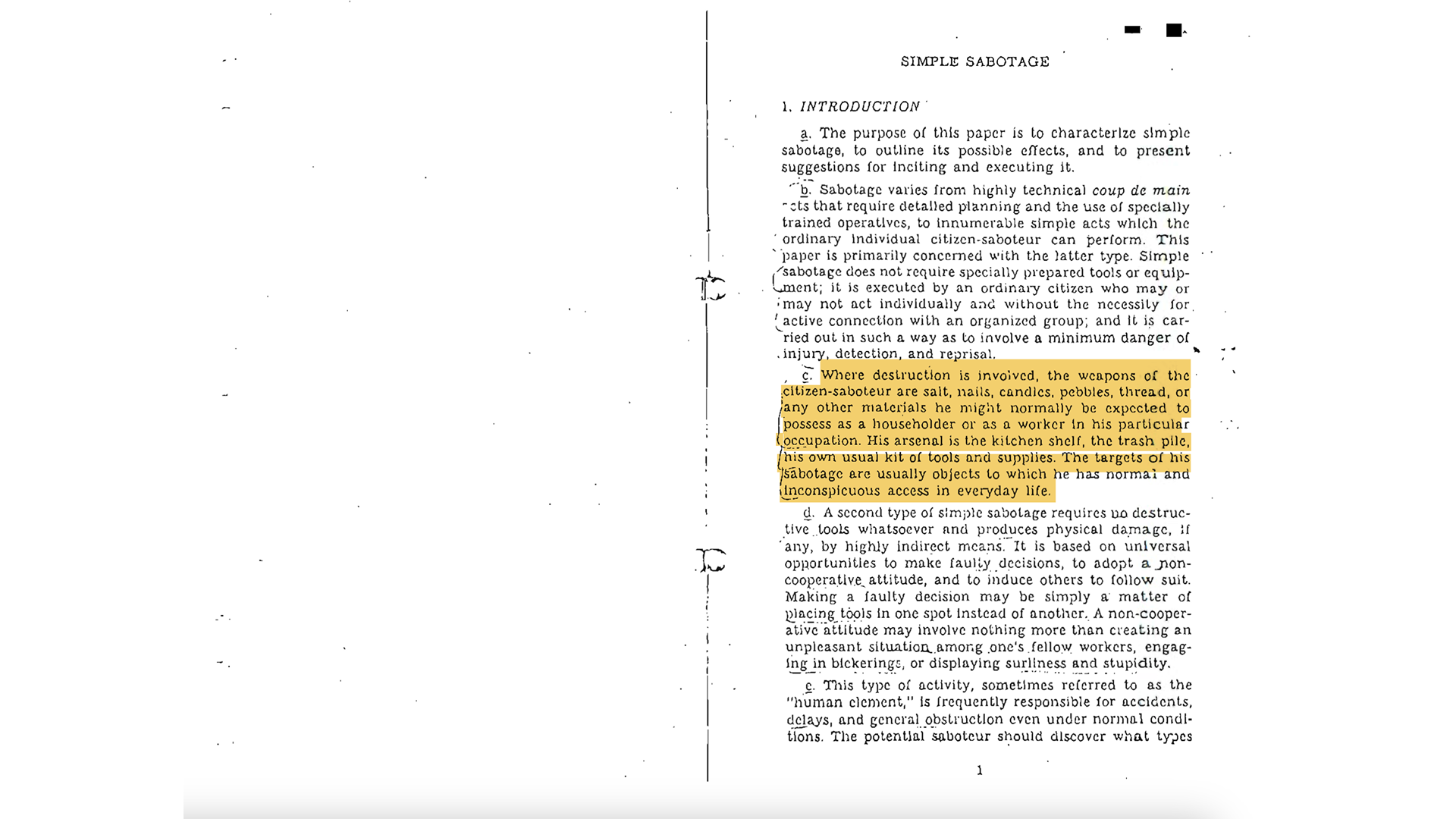

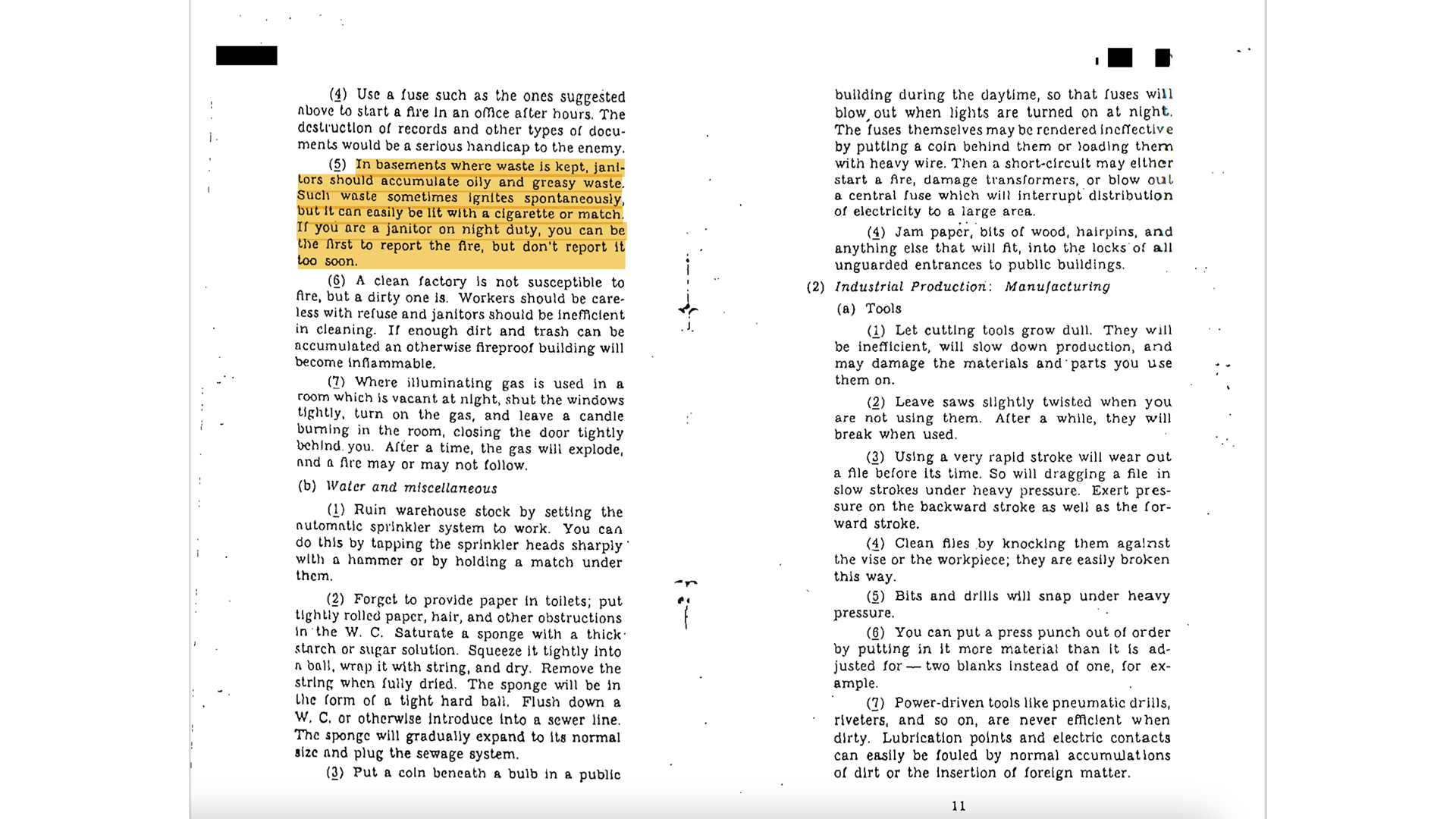

At my conference in February in LA, I talked about this amazing document called the Simple Sabotage Field Manual. The Office of Strategic Services—the precursor to the CIA—produced this document in 1944 as a way to encourage citizen saboteurs to quietly sabotage Nazi operations. Pass it out in France and encourage people to slow down the Nazis in whatever they were doing.

It’s a guide for these people to do this without getting themselves killed. The citizen saboteur, their weapons are salt and nails and candy. If you’re a janitor, one of the things you should do is leave a bucket of oily waste in the corner because that might catch fire. And if it doesn’t happen to catch fire, you can always throw a cigarette in it.

There’s a famous story about Citroën, the French car manufacturer, actually changing the line by a few millimeters on where to fill the oil in one of their trucks so that the Nazi trucks would break down more quickly because they would underfill the oil and it would run out.

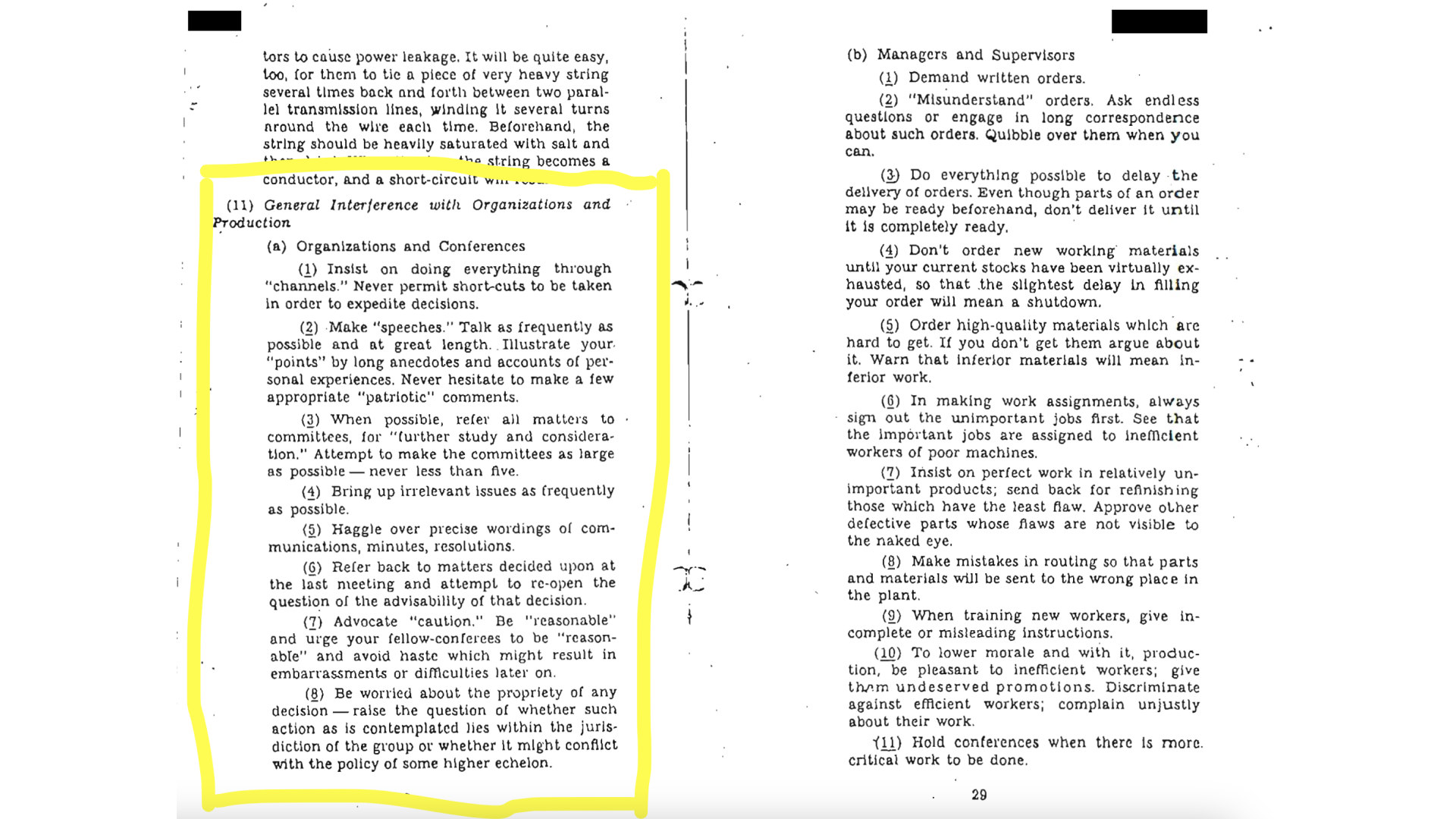

But the part that is most amazing about this document is towards the end when it switches from how to sabotage blue collar operations. This white portion is really an extraordinary document because it basically tells us how to operate in modern corporations:

- Insist on doing everything through channels

- Refer all matters to committees

- Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible

- Revisit previously made decisions

- Advocate caution

Anybody who wants to move too fast, make sure you tell them that they should slow down lest you become embarrassed by the decisions that you made. This is literally a manual produced by the United States with instructions on how to sabotage organizations.

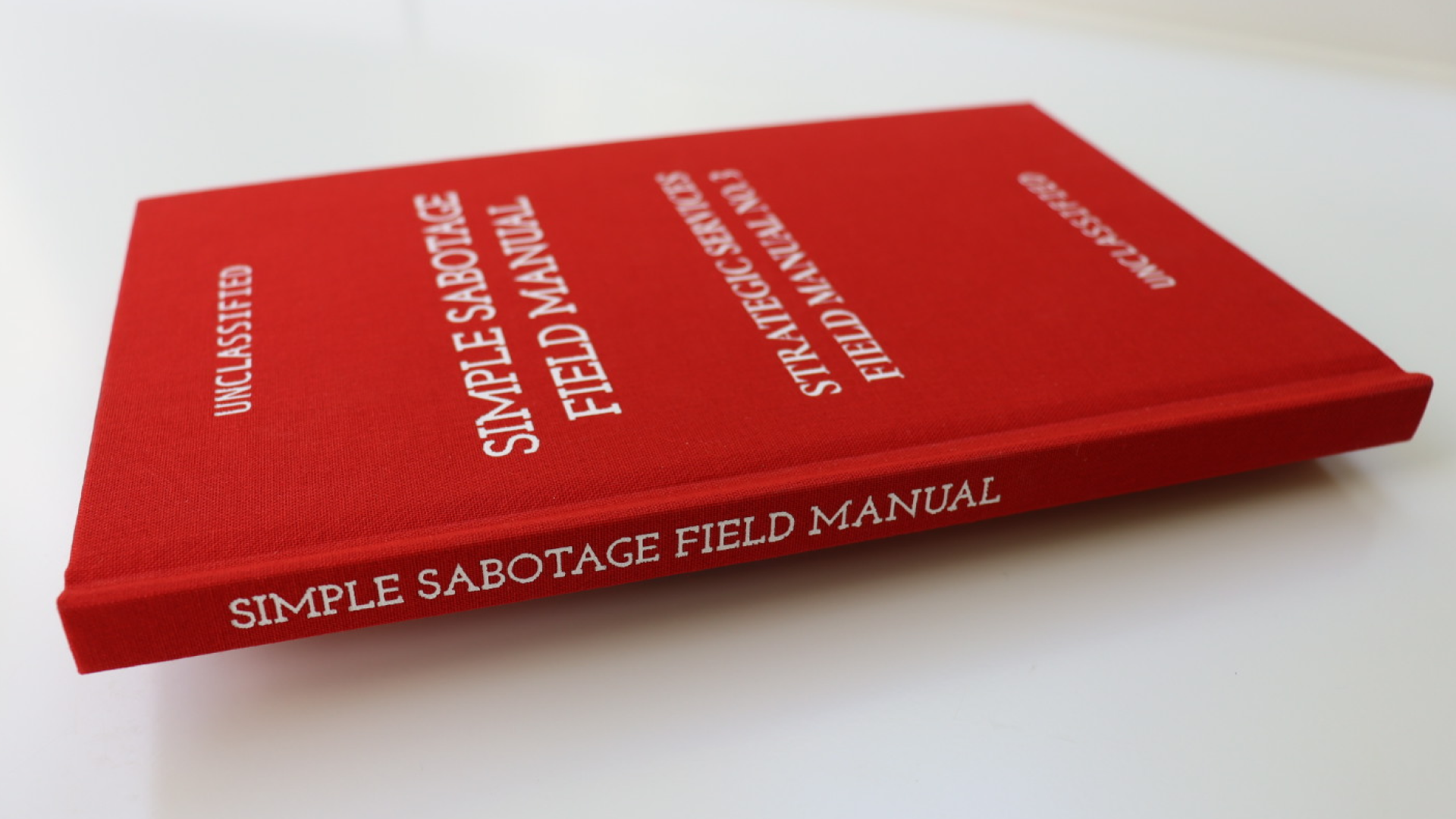

After the conference in February, I had this epiphany that because this was a good document produced by the government, it was in the public domain. So all of you hopefully have received a copy. Some of you are holding it, I see. We hired a designer. I wrote a foreword for it and we have republished this document in beautiful form.

You can all carry it with you and sabotage your own companies that way. Or at least you can hand it to folks and have a shared vocabulary for this kind of sabotage that happens. Those of us in this room, we’re pretty focused on moving things forward and probably moving slightly faster than our companies are always comfortable with. Building a shared vocabulary for how to deal with that I think is really critical. That’s our gift to you. Give it a read. We may put it up on Amazon at some point, but have fun.

So here we are. We are narcissists. We’re staring into the water and we see reflected back to us an org chart.

Fast Forward to 2025

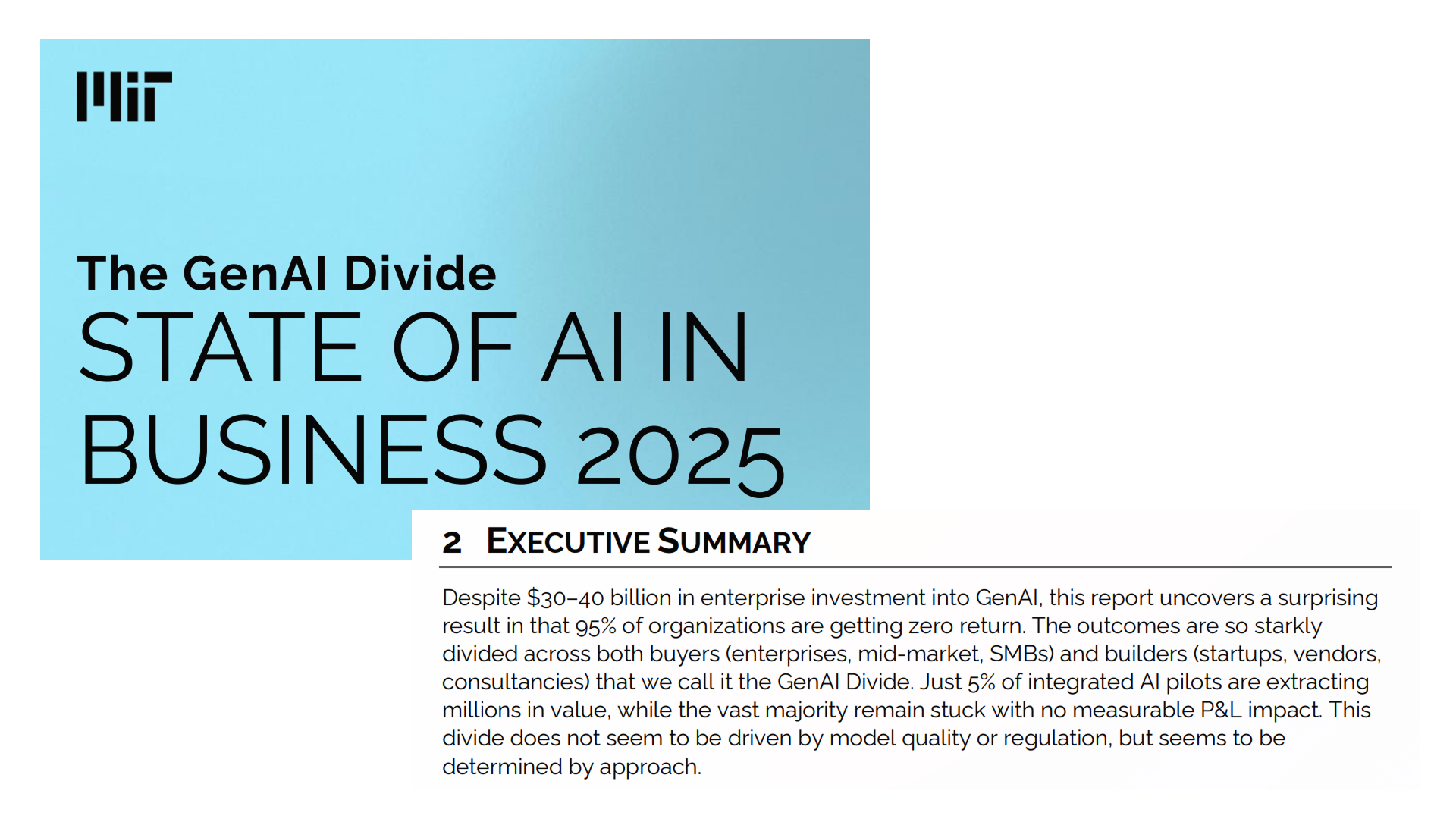

Fast forward to 2025. I’m sure all of you saw this document or this headline.

This is this MIT study that came out about a month ago that said 95% of AI pilots fail. Lots of people picked it up. It became a big thing. It’s got fairly questionable methodology. I don’t know how you actually calculate any of these things.

But actually having read the document, I think fundamentally the point of it is the point I made at the beginning. It’s just early. It’s really, really early in this process. We are in year three of what is probably a 10 or 15 year journey.

One of the things I said when we did the first version of this that I still fundamentally believe is if the models never got better than they were then—that was GPT-4—I thought we still have 10 years of runway to bring these into organizations and change the ways of working. Of course they have gotten significantly better and we still have 10 years at least to change the way we work.

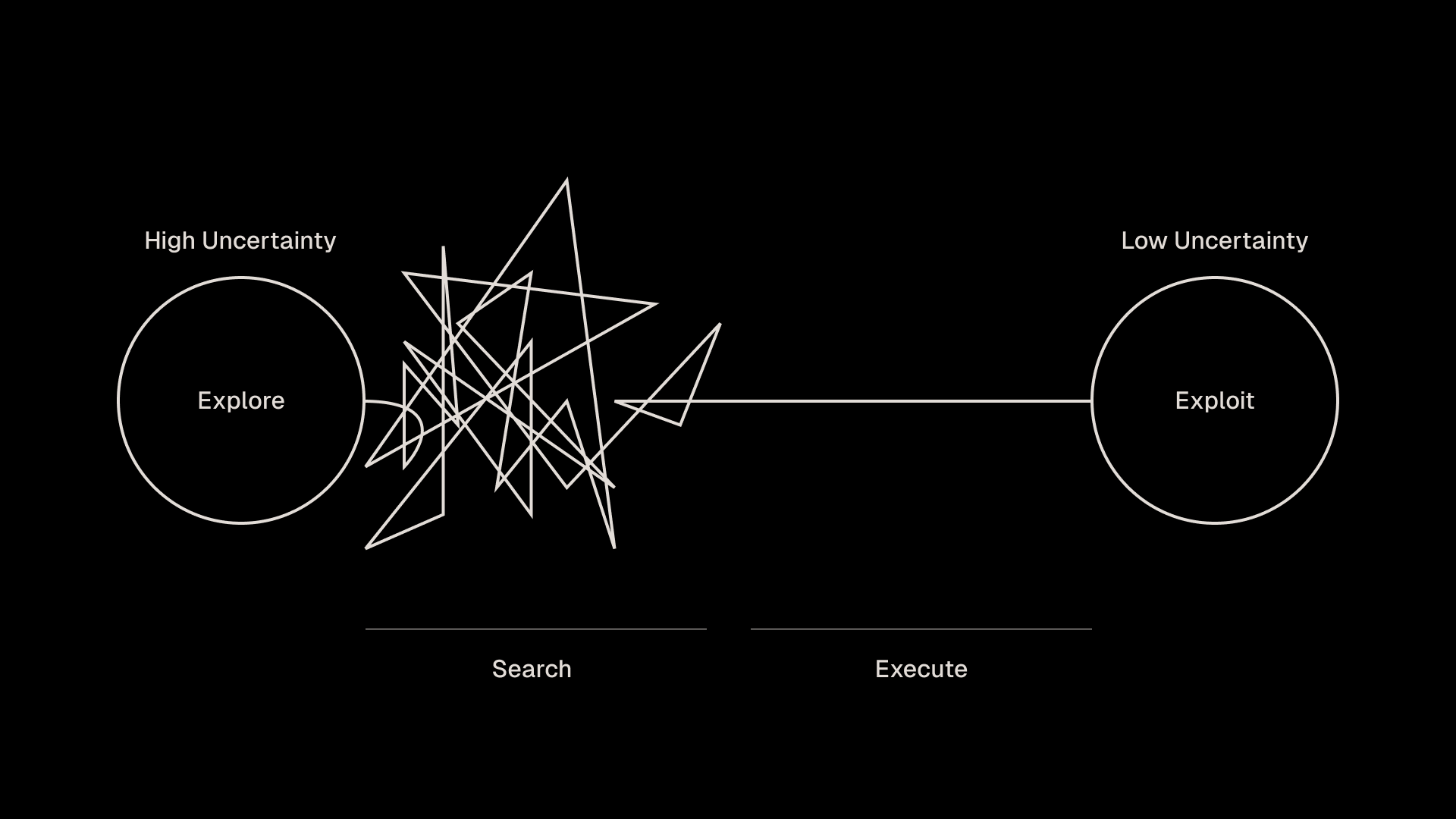

There’s this great idea in computer science called explore exploit. It’s a way you deal with problems when the problem essentially requires that you would have to try every permutation.

A thing we do every day that deals with this is using Google Maps for directions. Technically if you wanted to find the most optimal path between A and B using streets, the only way to find the perfect optimal path would be to try every single path. Obviously you can’t have Google Maps try every single path.

What Google Maps does is it spends some amount of time at the beginning searching the possible optimal paths and then it settles into one and optimizes from there. You realize that there’s a point of diminishing returns where you could keep searching forever and you would only get a one percent more efficient path to the place you’re going.

That’s the explore exploit trade-off. You have to do a wide search of spaces in explore and you do this narrow optimization in exploit.

I think this is also a perfect way to think about how companies work. There’s multiple trillion dollar companies represented in this room. A trillion dollar company is very much in exploit mode. A trillion dollar company has developed a business model that works really, really, really, really well. The whole existence of the organization is about how do you protect and drive the value of that investment. Everybody wishes they had that. There’s nothing wrong with that. Who am I to say that a trillion dollar company doesn’t understand how to operate its business? These are some of the greatest companies in the history of the world. But they are very much in exploit.

Part of the feeling that we get as practitioners who are trying to push AI inside enterprises is we push up against that. The company is built to optimize. It’s not really built for the exploration. It’s not built for searching over many permutations and trying different things and making those kinds of decisions.

A lot of what we feel in AI and elsewhere in this moment is that. We’re pushing up against the organization which is set up to do something different than the thing that we are trying to do.

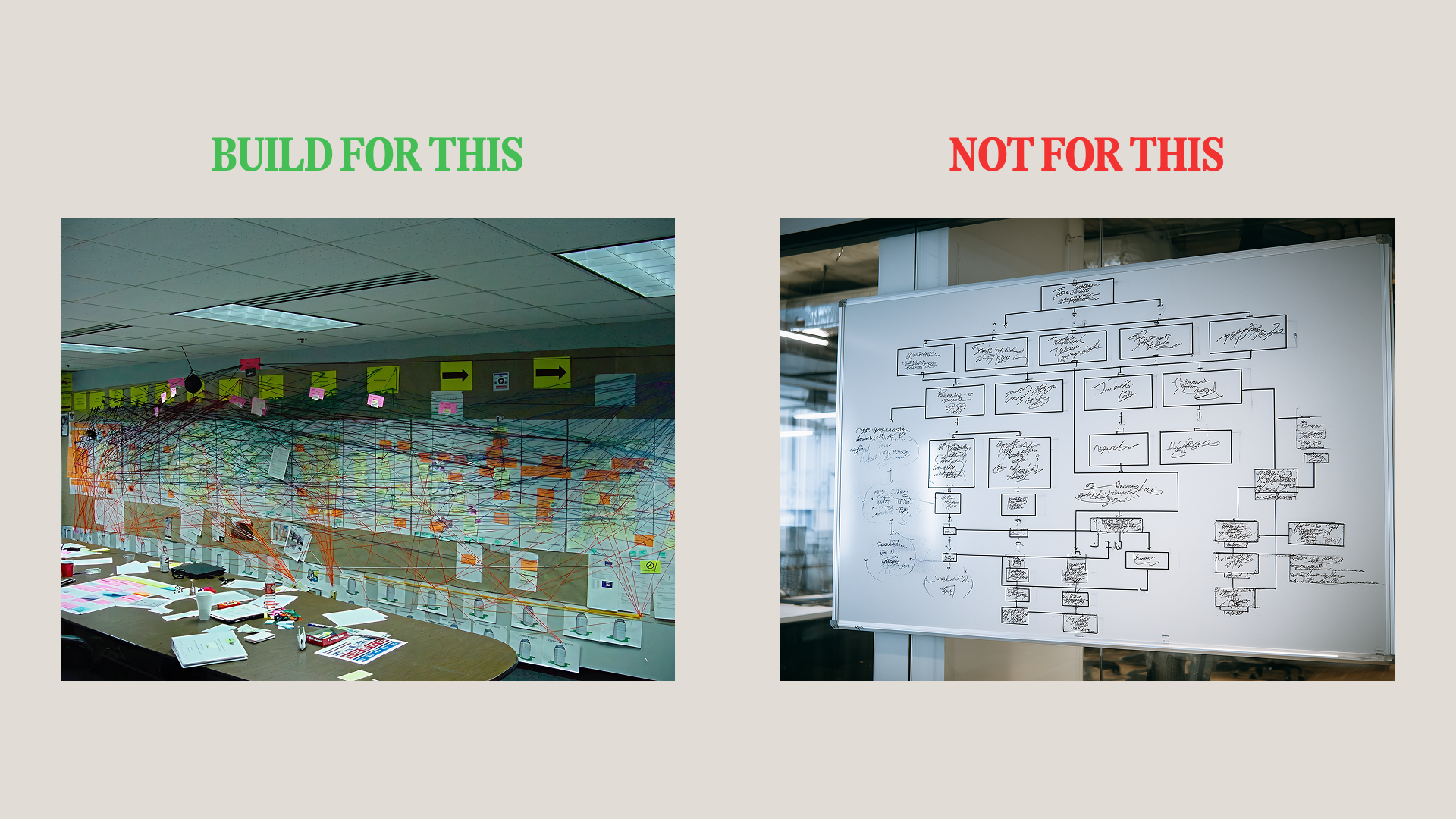

When you look at the actual quotes in the document, it basically says this. Most of these fail due to brittle workflows, lack of contextual learning, and misalignment with day-to-day operations. They’re falling over because they don’t actually recognize how the organization functions. They are trying to build for this perfect existence.

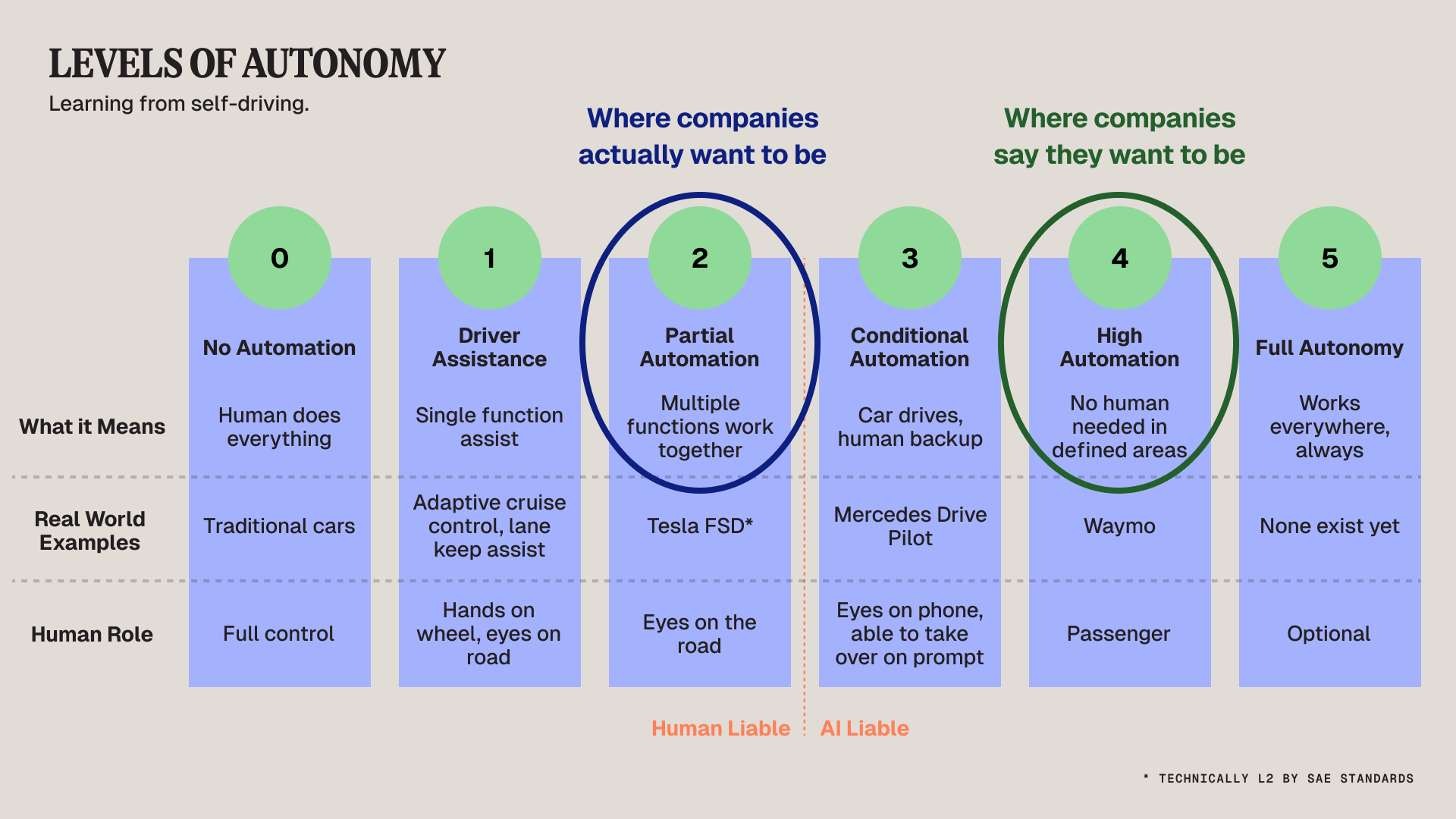

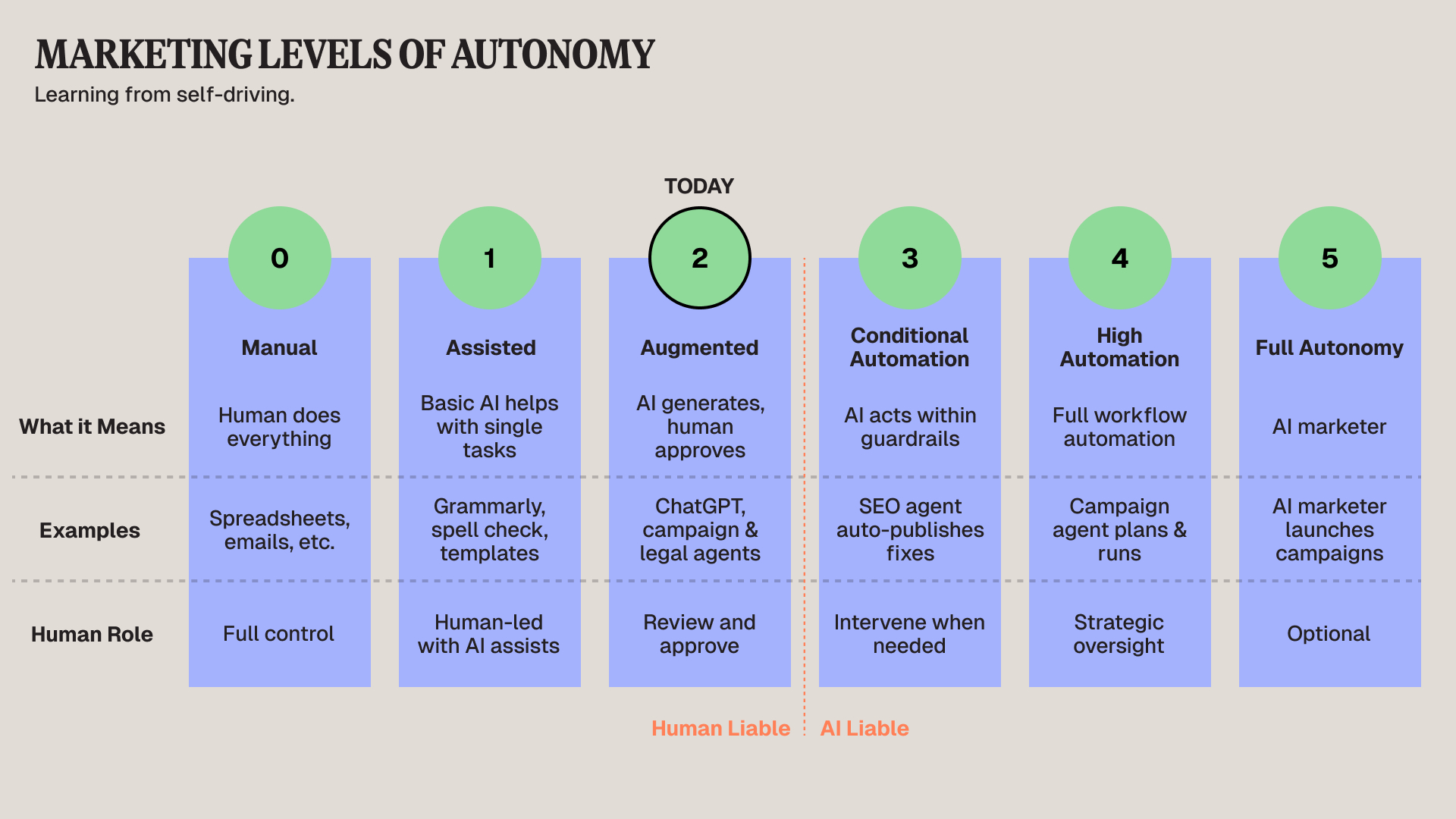

One of the other patterns I see here—this is the SAE levels of autonomy. In self-driving cars, you have these levels of autonomy. Tesla, as an example, is a level two autonomy vehicle. While it can do lots of amazing things, you as a human are still ultimately liable for what it does. If it gets into an accident, you are liable. Waymo famously is level four. You get in, you are not liable for anything that Waymo does.

One of the things that’s happening inside organizations right now is that you try to build this perfect demo. The perfect AI demo. It’s like this perfect level four demo. No people are going to touch it. And then it runs into the messy reality that is the organization. And it all falls apart.

The reality is that I actually haven’t met any large companies that don’t say that as marketers, you have to review all content AI produces before it goes out the door. This is just the reality of the situation we’re in. So why are we doing level four when we should be focusing on level two?

We just got to stop trying to build for perfection. And we just got to build for reality. This is where we are.

The Superglue Analogy

I watch a lot of YouTube with my kids. I’ve talked about this in the past. It’s a thing we do every night. But I find a lot of inspiration from it. One of them is this science channel called Veritasium. They had this perfect analogy for this, about how superglue works:

“Superglue in the tube is a liquid of identical monomer molecules. The molecule is ethyl cyanoacrylate. When you put it between two surfaces, the liquid flows into all the pores and crevices. Then the monomers start reacting with each other, joining to form long polymer chains. This turns the glue from a liquid into a solid. At this point, it can no longer be pulled out of the cracks and crevices. So it’s stuck in place. And the two surfaces are connected. If you’re ever trying to glue surfaces that are too smooth, this is probably the reason superglue sticks poorly. There are few crevices or pores for it to cling to. To fix this, you can sand the surfaces to introduce some texture. That way, when the liquid glue solidifies, it’s stuck in the cracks.”

I kind of love this as an analogy. We’re trying to build these pilots and demos on this perfectly smooth surface. Like what if our companies actually operated that way instead of the reality, which is much messier, but it’s actually the thing that we need. This is my nooks and crannies theory of AI—you need all those nooks and crannies to make it actually work.

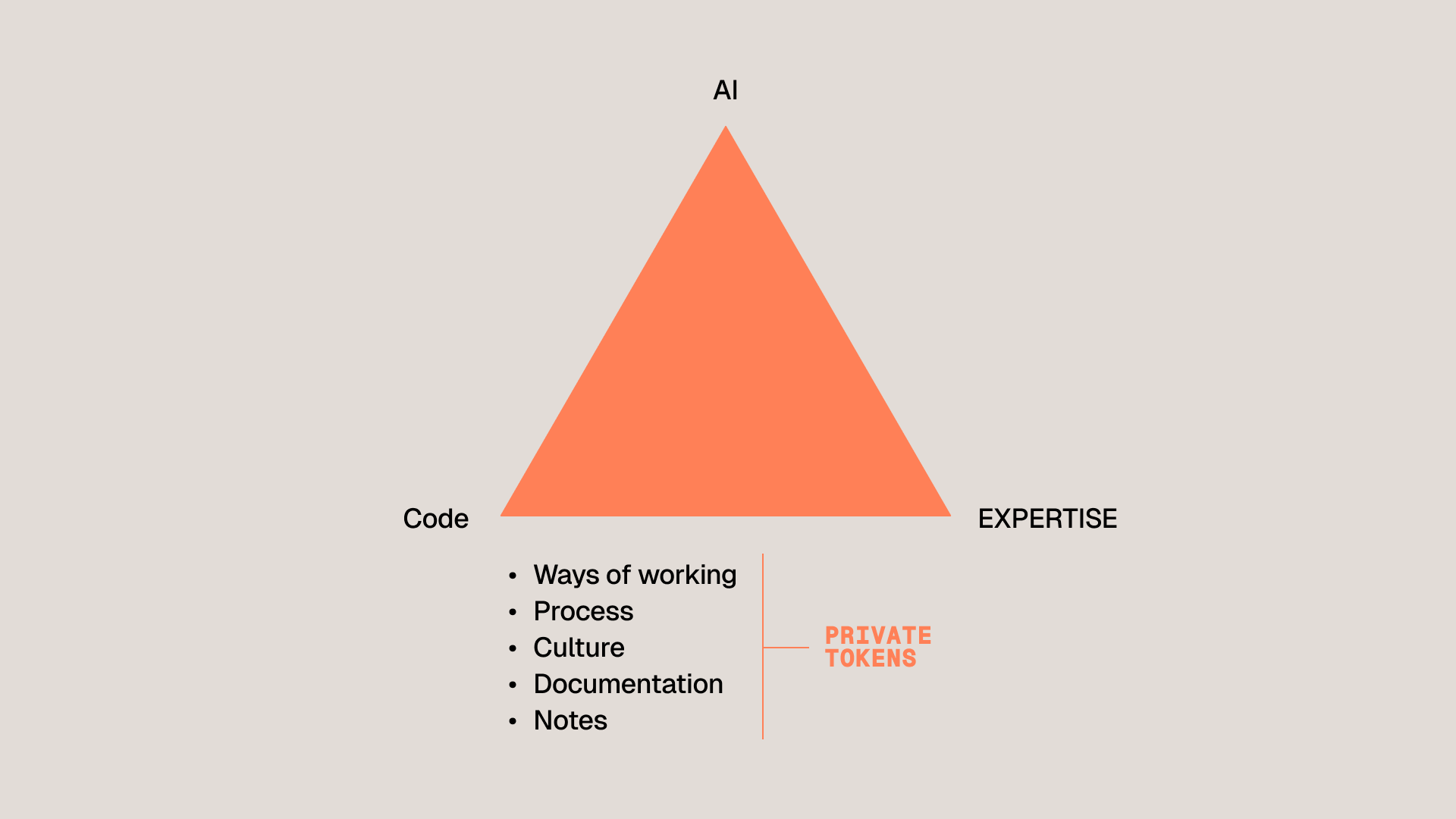

To me, the holy trinity of being successful in these AI programs is AI (which represents unmetered intelligence), code (which allows you to build workflows), and expertise (all the thinking and ideas and documents that exist inside the organization that make the organization actually work). That stuff at the bottom—you can’t do it without that. Without it, it’s just a demo. It’s going to be one of the 95% that fail.

In essence, we have to build for what’s on the left, not for the one on the right. There’s actually this theory from the 70s called the garbage can theory of organizations. The garbage can theory basically says rather than this perfect org chart, the way organizations actually work is we put a bunch of people and problems and money and all these things into a big garbage can, and we mix it up. What we get out is randomly assorted groupings that solve really hard problems really amazingly well.

It’s not that this is a problematic thing, or we need to fix it. This is just the reality of how we function. In urban planning, we call these desire paths. They’re these lines that develop when people walk over a path.

So bureaucracy, I think, interestingly, in a way, is the substrate that we need to make these things work. We don’t want to ignore it. We actually want to build into it. We don’t want to pretend that we don’t need approvals by all of these people along the way. We just need to think about that. We need to build systems in different kinds of ways. When you’re building an agent to write copy, you need to think about where in that process people are going to need to intercede, because people need to intercede, and that’s fine. That’s where you are.

Why This Works: Transformers

All of this works because these models introduced in 2017 called transformers were built on this thing called self-attention. This is as deep as I’ll go technically. I’ve tried not to go too deep.

It’s called self-attention. Essentially, every time you input into the model, you ask it a question—like in this case, “Why is AI a mirror, not a crystal ball?”—what it does is it takes all the words from that input, and it compares it to all the other words in that input. It compares each one to each other.

It looks at them not based on the order that you put them in or anything else. It runs it through a bunch of specialized systems that basically say, what should attend to what else? Basically, which connections are most important?

In a way, I think it’s very representative of those desire paths. It finds the reality of the connections, not the ones that we say. This is what it’s able to understand. What’s amazing about that is that it means it’s the first kind of software system that can understand that messy reality. All of these other input methods we’ve had for computers over the last 100 years have been based on being very orderly. It starts with punch cards, then we have terminals, then we have GUIs, and you always have to click on a thing. I really do think this is this amazing moment where we can have these messy inputs and messy outputs, and it can make sense of any of them.

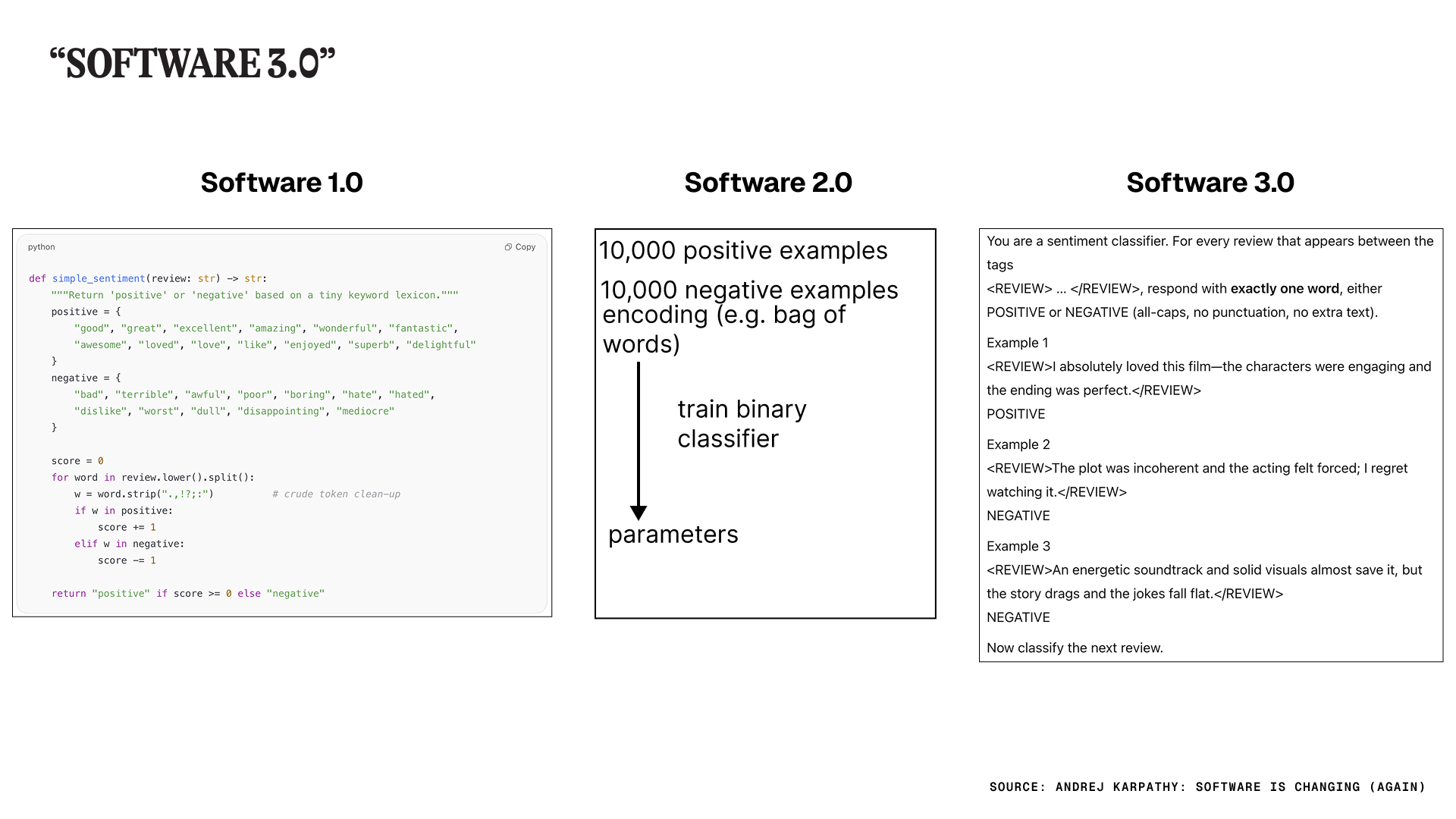

Andrej Karpathy, who ran AI at Tesla for a while and was one of the first engineers at OpenAI, calls it software 3.0. Basically, if you’re trying to solve a problem in software 1.0, like doing sentiment analysis, you’d write a bunch of code. Software 2.0 was neural nets—you’d take a ton of examples and train your own neural net to do sentiment analysis.

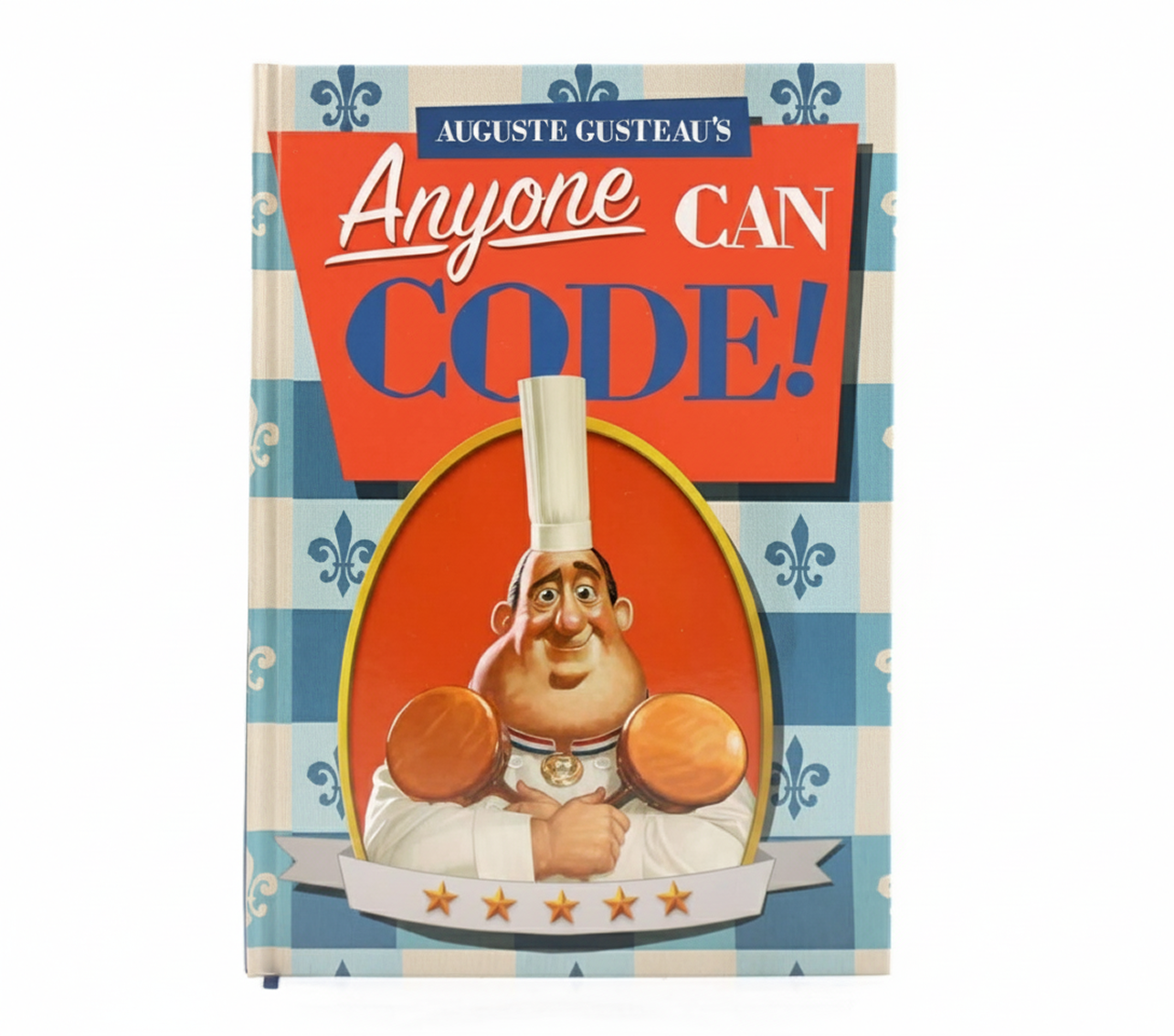

In example 3, you can just write a prompt. We can all ask ChatGPT, we could open our phone right now, and we can do sentiment analysis. Obviously, the amazing difference between those three things is: one and two, you definitely had to be an engineer, and three, you definitely do not.

That’s the moment we’re all dealing with, but it’s also that it makes it so we can interpret a whole new kind of data. We move from needing very structured data all the time to being able to take in qualitative and creative information and process that.

Everything Becomes Software

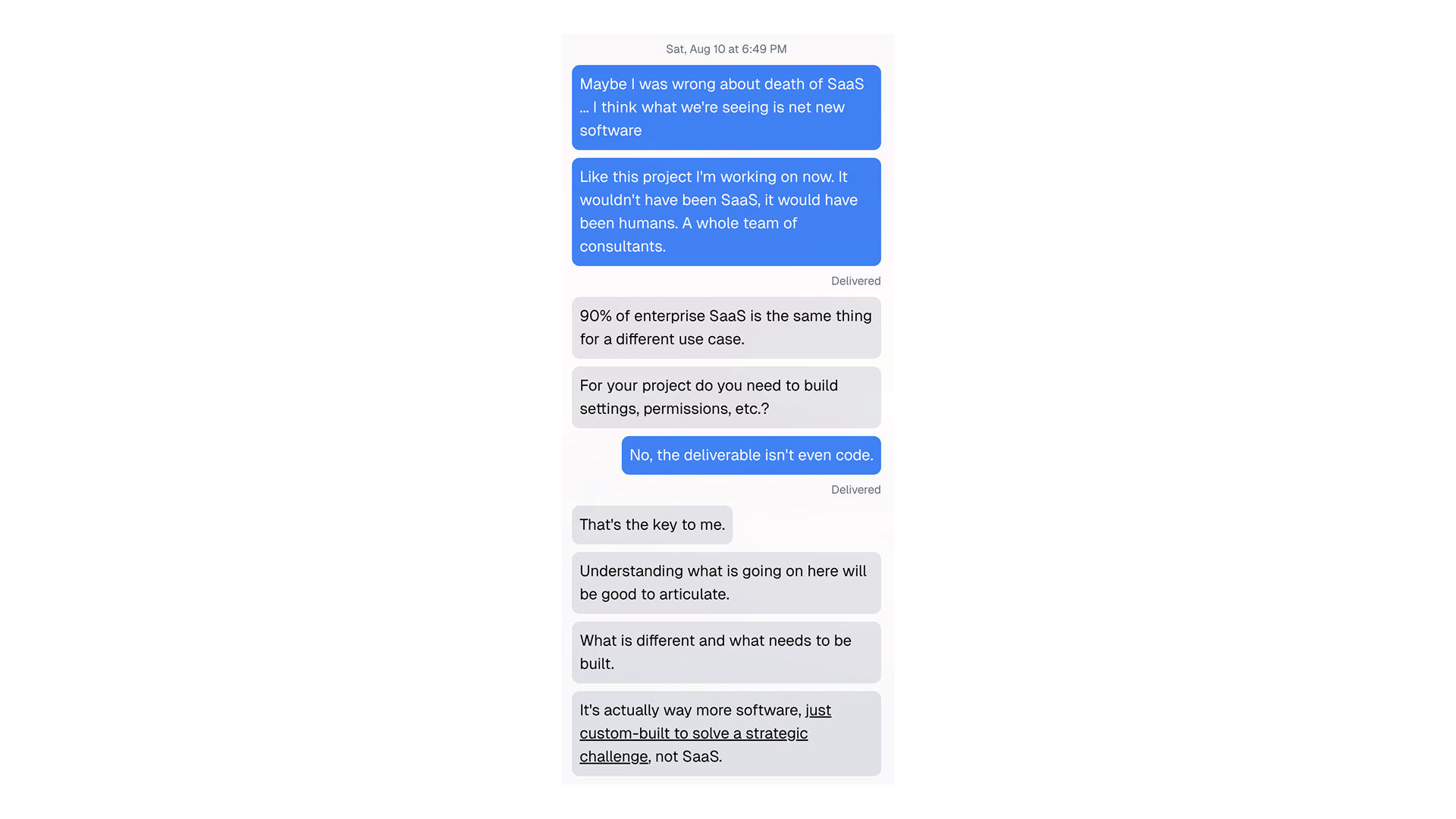

I had this conversation with James—my co-founder at Percolate, co-founder at Alephic—after I was working on a project with EY a little over a year ago. They’re going to talk about it a little later. I had this realization that I was using code and AI to do something that would have taken 20 people over multiple months to do. That was a mind-blowing thing.

The mind-blowing thing wasn’t so much that AI was replacing SaaS. It was that this is a whole new world of software that we can start to build. It just wasn’t a place that software could touch before.

I think that’s the thing I’ve been going over and over in my head: this moment, what’s so incredible about it, is that we can turn anything into software. It’s not about adding AI to software, though there’s a lot of that happening as well. It’s about turning anything, any process, into software.

Turning the very qualitative—and what we do as marketers tends to be pretty qualitative and pretty creative—the opportunity to apply these software development principles to these kinds of problems I think is a really amazing thing.

Just as a small example of this, the way I talked at the beginning about writing my presentation. I use this note-taking system called Obsidian. You write a bunch of markdown notes. Now I use it with Claude Code. I’m able to do all of this writing and all of this work, then save it, use tools like Git, and I can see the whole history. I can watch that whole presentation get written.

Even more mind-blowing—I had to add this yesterday because it was such a good example—is what I do when I’m writing the presentation. I basically go back and forth. I start in this script, then you go to slides. Naturally when you take a written essay and turn it into slides, you need to change a bunch of stuff. There’s things you get away with like just adding a heading to change things—that’s a little harder to get away with when you’re actually talking to 200 people.

What I had to do is I downloaded the PDF, then I had it split all the images out. I had it run every image through AI. Then I had it take my script and put all the images into the script, and rework the ordering of the script based on the ordering I had actually put into the images. Then I could review it and refine it. I could also send it over to ChatGPT and Claude to get feedback on it. In addition to each image, I had to describe what was in the image, so it could read the script as a whole, read the talk as a whole, and give me specific feedback on the places that I needed to work on it.

In one way this moment is amazing because anyone can code.

But I think even more amazing is that anything can be code. That’s awesome. I mean it’s scary, it’s different, but I think it’s pretty amazing.

In essence, this is my theme for the day: AI isn’t so much a software feature as it is this missing interface between marketing and computing. It lets us start to think about new ways of doing our jobs, our tasks, and all the things that we might want to do.

Wrapping Up

So I said a lot, I’m going to attempt to wrap this up fairly quickly. Some of these wrap-ups also are more general thoughts.

Leaders have to be in the trenches. This is a huge one. Those of you here, you largely are in the trenches, but I think leaders especially have to be hands-on keyboard to get this.

There’s this great quote from Andy Grove in Only the Paranoid Survive where he basically says that in an inflection point, you’ve got to throw everything away, and you’ve got to let chaos reign. I think that’s really kind of what’s going on here.

Bureaucracy is the substrate. Obviously we have to push against it. We’re pushing to build. Those of us in the room are builders. But we don’t want to ignore the bureaucracy, because we need that to grip into the organization, to build things that are actually useful. When you think about what those are: ways of working, documentation, all the amazing thoughts that exist in the heads of people.

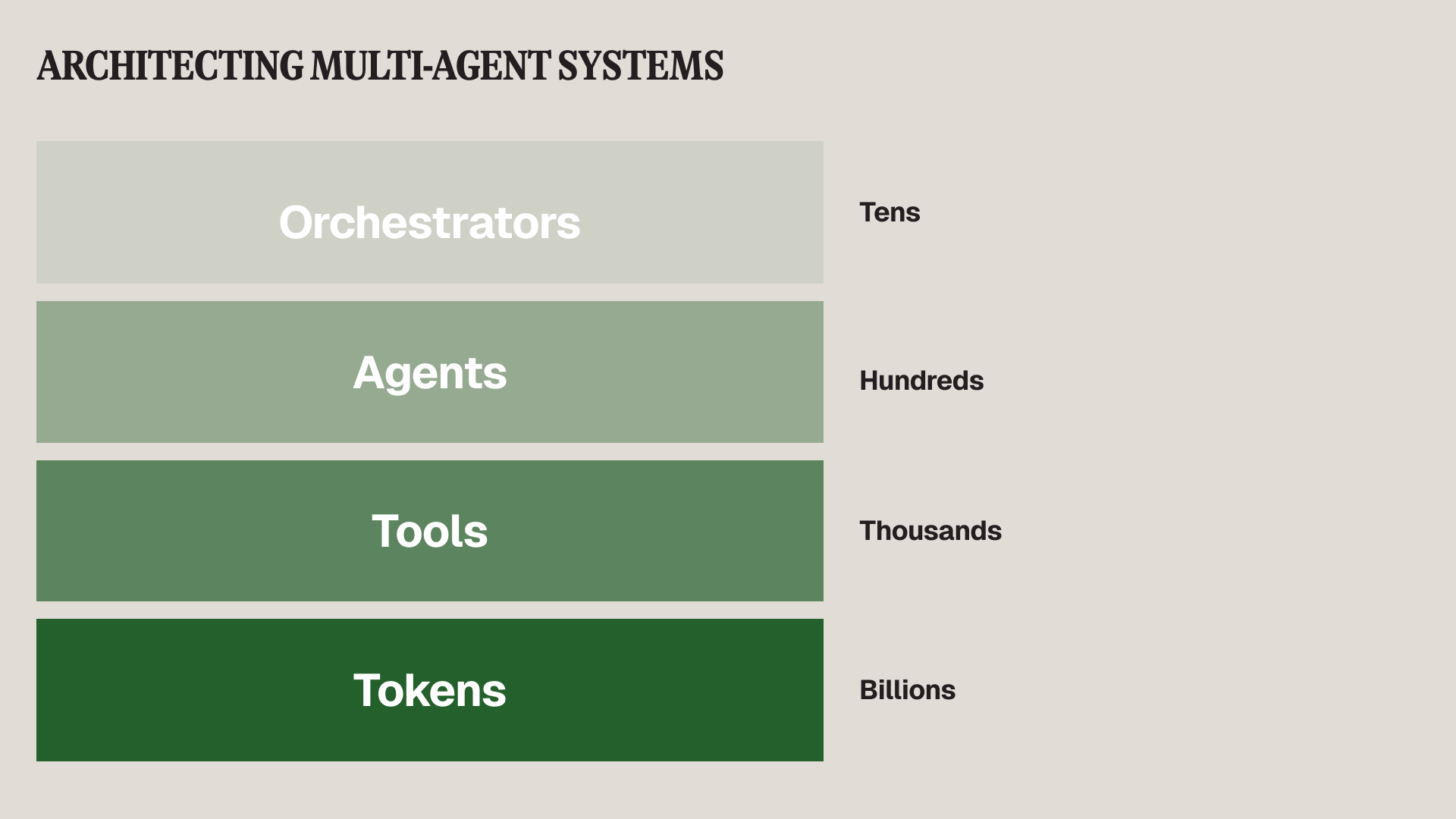

Start with tools, not orchestrators. Agents is a thing that comes up in every single meeting that I ever go to now. There’s a very simple thing to understand about agents. When you actually look at how they’re built, like you look at something like LangChain or AWS Strands, what you see is this model for how they work.

At the bottom you have these tokens—both the public tokens the models been trained on, and your private tokens, all the documentation and expertise that you have. Then you have tools—little bits and pieces that do something very narrow: search the web, grab a web page back. Agents ultimately are groups of tools, and orchestrators are groups of agents.

The key is you got to start from the bottom up, not the top down. Too many organizations who fall over that 95%, you start from the top, you try to build the whole thing, you try to eat the whole animal at once, instead of breaking it into pieces.

Build level two, not level four. I talked about this, but I think just building for reality over perfection.

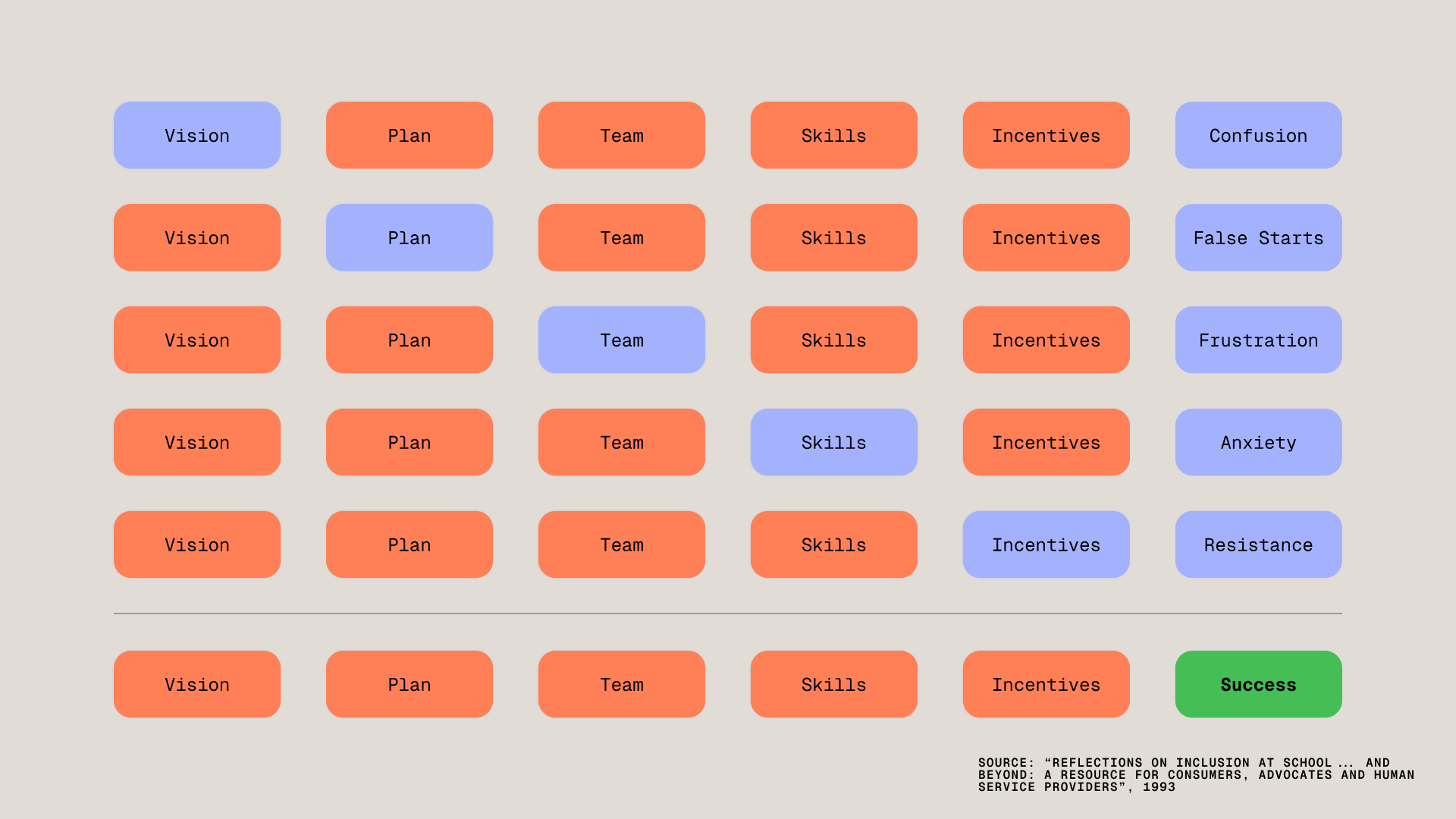

Finally it’s one percent inspiration, 99% perspiration. At the end of the day, as much as this is a technical problem, it’s a change management problem.

This is my favorite change management framework. I hope you all have a favorite change management framework as well. This comes from education in the early 90s. It’s a really amazing way to think about how you drive change. The point of it is that if you’re missing any one of these pieces, what you get on the other end is confusion and false starts.

Final Truths

Finally returning to the four plus one truths:

It’s early. I think that’s still very true.

Hands-on is the only way. Hopefully you are all hands-on in this room. If you’re here, that’s probably why you’re here. But we’ve got to encourage others, especially the leaders in the organizations to also be hands-on. I think that’s really critical.

Don’t trust anyone who sounds too confident, including myself or anybody else who shows up on this stage.

AI is a mirror, not a crystal ball.

The last one is just stop apologizing. We gave away these bracelets. It started as a joke on our Slack. Basically it says WWGPTD—What Would GPT Do. We would use it to just tell people, hey, if you’re asking a question that could easily be answered by AI, why don’t you just go ask AI first.

There was a study that the journal wrote up recently that there’s an emerging gender gap in AI usage. Women are less likely than men to be using AI because they’re worried that it’s going to make them look like they aren’t good at their jobs. We’ve just got to kill that across everything. Generally we encourage people to use the best technology available to them within their organization. This is the best technology available to them. We should encourage people to use it, and we’ve got to take away any of that stigma.