In the 1980s, economist Mancur Olson delivered a stark warning about what happens as systems grow more complex and stable. Olson observed that societies accumulate "distributional coalitions"–special interests, rules, and organizational layers–that gradually slow progress. In such complex systems, those who excel at navigating the bureaucracy tend to be rewarded, which perversely incentivizes even more complexity. This leads to institutional sclerosis, where decisions become bogged down, groups fixate on protecting their share, and the best talent shifts from innovation to process navigation.

Olson's thesis, laid out in his 1982 book, The Rise and Decline of Nations, revealed how stable, prosperous societies can gradually choke on their accumulated organizational complexity. The longer a system remains unchanged, the more layers accumulate, each resisting change and slowing down adaptation. While Olson's insight was originally about nations and governments, the same dynamic applies within large organizations, creating a paradox where success breeds the very bureaucracy that can eventually undermine it.

Alephic Newsletter

Our company-wide newsletter on AI, marketing, and building software.

Subscribe to receive all of our updates directly in your inbox.

Bureaucracy Invades the Corporate World

As startups grow into established companies, they follow a predictable trajectory: processes multiply, hierarchies become more complex, and internal politics intensify. The nimble culture that drove early success gives way to bureaucratic management systems. In large corporations, even simple decisions often require multiple approvals, and talented employees spend more time on compliance and internal video calls than on solving customer problems. As historian C. Northcote Parkinson observed, "the number of workers within a bureaucracy tends to grow regardless of the amount of work to be done." This adage—known as Parkinson's Law—captures how bureaucracies self-perpetuate through expanding management layers.

Few illustrate this pattern better than DocuSign, the e-signature platform that transformed contract processing. As of 2024, DocuSign employed approximately 6,840 people, down from 7,330 following a 6% workforce reduction. About two-thirds of that headcount was dedicated to sales, marketing, and customer success, reflecting the significant resources required to secure and support enterprise contracts. For comparison, Zoom employed around 7,400 people for its broader collaboration suite, which arguably presents much more complex technical problems to solve, with approximately 40% of the workforce dedicated to sales and marketing.

DocuSign's 2024 restructuring highlights a supreme irony: the very company whose mission was to eliminate paper shuffling has created a digital bureaucracy. In its quest to eliminate physical document routing, DocuSign built virtual corridors filled with administrators pushing pixels instead of paper. The shuffling hasn't disappeared—it's merely transformed from atoms to bits, perfectly illustrating Olson's warning about institutional sediment.

That’s not to say all hierarchy is harmful. Organizations need structure—clear roles and processes prevent chaos. However, there is a tipping point where a healthy hierarchy mutates into a bloated bureaucracy. In theory, hierarchy adds value through effective supervision and communication. In practice, bureaucratic layers add friction: communication slows, leaders focus on turf protection, and employees learn that following rules is safer than proposing novel ideas. As anthropologist David Graeber explained in The Utopia of Rules, bureaucracy becomes "marked by officialism, red tape, and proliferation," where rule-keeping displaces problem-solving.

Having achieved product-market fit, companies naturally pivot from exploration to exploitation, scaling and standardizing what works. This operational shift is rational, meant to safeguard profitable routines, even as it deepens bureaucratic tendencies.

The Bleed of Bureaucracy

In 1968, software engineer Melvin Conway observed that "organizations which design systems are constrained to produce designs which are copies of their communication structures." This insight, known as "Conway's Law," reveals that organizational structure directly maps onto the systems built. When silos and layers fragment communication, the resulting products inherit this fragmentation, manifesting as duplicated features, complicated user flows, and disconnected modules that mirror the org chart.

Conway's architectural mirroring and Olson's institutional sclerosis represent two manifestations of the same problem—one affecting product design, the other organizational agility. Over time, procedures accumulate, and agile cultures morph into something resembling civil service. Focus shifts from customer delight to internal committee approval. Employees quickly learn that proposing bold initiatives carries more career risk than completing routine paperwork.

The Innovation Killer: How Complexity Stifles New Ideas

Perhaps the most damaging effect of mature bureaucracy is its suppression of innovation. When an organization's primary mandate becomes defending and scaling its profitable core (exploitation), breakthrough ideas become secondary considerations. The control systems designed to protect margins, such as committees, cross-functional sign-offs, and stage gates, simultaneously slow down experimentation. When every proposal must navigate approval gauntlets, employees redirect energy toward maintaining existing systems rather than reimagining them. A risk-averse culture emerges where incremental tweaks survive but bolder bets wither, directly impacting productivity and growth potential.

Organizational-behavior research explains why this structural shift is both logical and limiting. In the 1960s, Tom Burns and G. M. Stalker distinguished between mechanistic and organic designs. Mechanistic systems—characterized by rigid roles, strict hierarchies, and top-down control—excel at exploitation, efficiently scaling what is already known in stable markets. Organic systems—looser networks encouraging experimentation—better serve exploration when conditions are uncertain. The trade-off appears when the very controls designed to protect proven models impede adaptation to shifting landscapes.

The Productivity Penalty: When Growth Stalls Under Bureaucracy

Bureaucracy imposes substantial costs on productivity and innovation. Research shows a strong correlation between rising administrative overhead and declining productivity growth. In the United States, managerial and administrative roles expanded to approximately one for every four to seven frontline workers by the 2010s—a significant increase since the 1980s.

Tech companies now track this dynamic through the "builder ratio"—the proportion of engineers and other creators relative to managers and process roles. Amazon instructed every division to improve its individual contributor-to-manager ratio by 15 percent, while Microsoft launched parallel efforts to reduce the number of program-management layers. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy explained the rationale: "If we do this work well, it will increase our teammates' ability to move fast, clarify and invigorate their sense of ownership, drive decision-making closer to the front lines where it most impacts customers (and the business), decrease bureaucracy, and strengthen our organizations' ability to make customers' lives better."

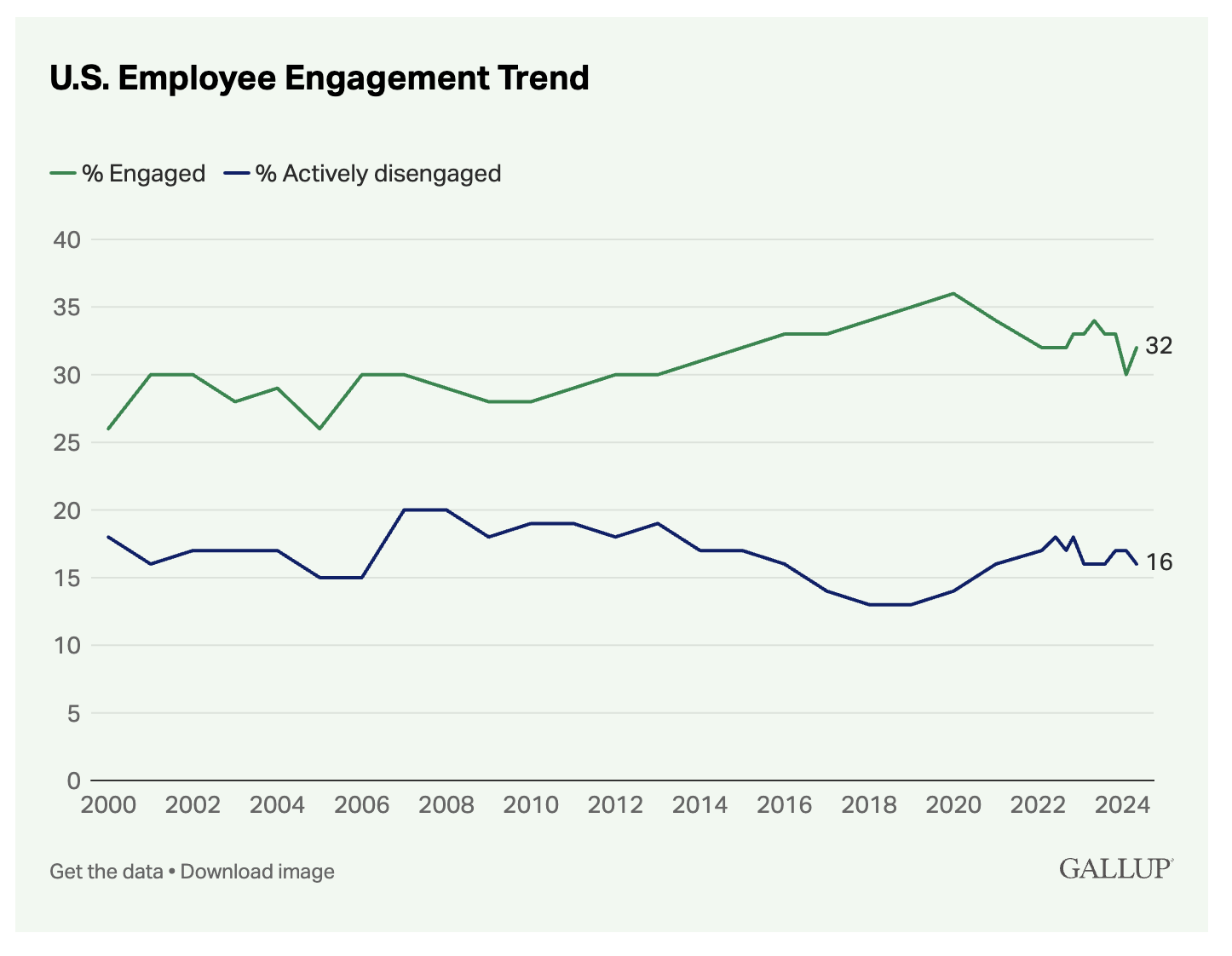

From a macroeconomic perspective, a 2016 Harvard Business Review analysis estimated that U.S. bureaucracy costs approximately $3 trillion in economic output annually, roughly 17 percent of GDP at that time. The human toll is equally severe: Gallup reported that only 32% of U.S. workers felt engaged at work in 2024, with excessive paperwork and unnecessary meetings cited as primary obstacles.

The irony is pronounced in organizations founded to eliminate inefficiency that subsequently become burdened with their own internal paper-pushing. For every frontline employee focused on customer value, multiple others manage internal processes and approvals. The bureaucracy intended to ensure accountability, but instead created workflow congestion, stifled creativity, and ultimately degraded customer experience—classic symptoms of Olson-style sclerosis at the corporate level.

Unlocking Abundance at Scale

Bureaucracy began as a rational safety mechanism: after finding product-market fit, companies pivot from exploration to exploitation to protect their revenue engines. However, without vigilance, these safeguards morph into self-sabotage, slowing the very innovation needed to maintain competitiveness.

The Abundance Agenda: Beyond Scarcity Without Sprawl

This ability to create coherence without requiring structure, to embrace plurality without chaos, is the key to abundance without bureaucracy. This concept is gaining momentum across various domains. In their 2025 book, Abundance, Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein argue that excessive administrative burdens create artificial scarcities in multiple sectors, advocating for a fundamental rethinking of productivity and innovation.

Historically, creating abundance meant accepting standardization and complexity. To scale operations, organizations needed uniform data models, workflows, and approaches. This forced trade-off between abundance and coherence led to bureaucratic expansion as a necessary cost of growth. Transportation infrastructure exemplifies this pattern perfectly—traditional systems required enormous bureaucratic structures to standardize roads, traffic laws, vehicle regulations, and licensing systems, all designed around human capabilities and limitations. Self-driving vehicles represent the paradigm shift AI enables: rather than requiring completely standardized infrastructure like railway systems did, autonomous vehicles use AI to adapt to diverse existing environments, interpreting varied road conditions, traffic patterns, and driving cultures without forcing uniformity. The technology functions as an interface layer that handles complexity, allowing abundance (widespread mobility) without the historical bureaucratic overhead.

AI fundamentally changes this equation. For the first time, abundance no longer requires standardization. Different systems, data models, and approaches can coexist because AI serves as the translator between them. Rather than forcing conformity, AI adapts to existing structures, allowing organizations to pursue abundance without the traditional bureaucratic overhead.

Consider data integration: previously, connecting systems required expensive middleware and rigid standards. Now, AI can interpret and translate between disparate data models in real-time. Sales data can be written in natural language, automatically structured for databases, and analyzed without requiring employees to complete standardized forms in systems like Salesforce.

Strategies for Breaking Through Bureaucratic Inertia

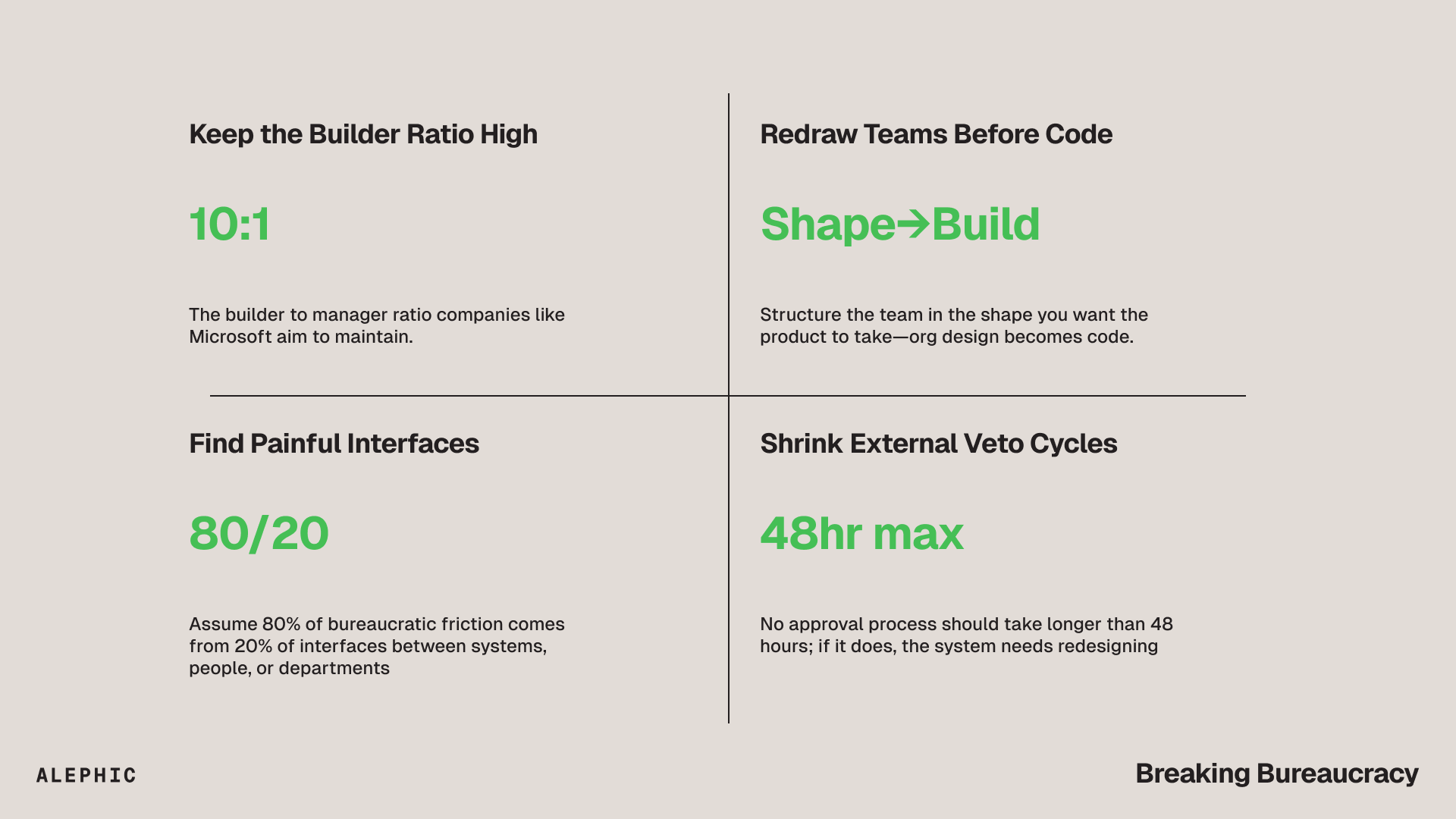

- Keep the builder ratio high. Tech companies like Amazon and Microsoft actively track and optimize the ratio of individual contributors to managers. This emphasis on maximizing builders versus administrators creates faster decision loops and fewer territorial disputes, delivering more value with the same resources.

- Redraw teams before code. Employ the "inverse Conway maneuver" by proactively reorganizing teams around desired product outcomes. If Conway's Law holds, then restructuring teams can prevent bureaucratic patterns from hardcoding into tomorrow's products.

- Find painful interfaces. Identify information bottlenecks where data transfers between systems or departments. These friction points—requiring executive sign-offs, format conversions, or cross-functional approvals—represent prime opportunities for AI implementation. Look for places where people spend time translating between systems or waiting for approvals, and introduce AI as a flexible interface.

- Shrink external veto cycles. Thompson and Klein's abundance agenda advocates for permit processes measured in weeks, not years. Apply this principle internally by streamlining approvals, reducing the number of sign-offs, and implementing time limits on reviews. Projects should progress from idea to implementation before market conditions shift or momentum dissipates. If you don't trust your people, find new people.

These approaches create, oxymoronically, "lean complexity"—a dynamic balance where exploitation funds exploration, innovation continuously renews core offerings, and bureaucratic structures serve organizational goals rather than perpetuating themselves. AI's capacity to translate between systems, people, and processes enables organizations to achieve both abundance and coherence simultaneously, representing perhaps the greatest opportunity to overcome organizational inertia in a generation.